Regional War Rooms

When in 1948, spurred on by the developing Cold War and the Berlin crisis, civil defence was reintroduced the Civil Defence Joint Planning Staff quickly laid down the basis for a new civil defence structure for Britain. Early in 1949 they recommended the provision of “protected control rooms with signal communications at local authority, zone, region and central government level”. This lead to the setting up of the Working Party on Civil Defence War Rooms which initially concentrated on planning war rooms for the civil defence regions which had been re-established based on those used in World War II.

The Working Party only considered sites in England and Wales as Scotland and Northern Ireland had their own civil defence arrangements. The Working Party decided to leave London out of its initial plans because its size and potential as a target meant it would have to be treated as a special case. The sites proposed were all in the same regional centres as their wartime predecessors but they would be “outside the central key area of the regional town…where adequate communications can be provided with civil and military headquarters in the region and with the Central War Room in London”. Building the War Rooms did not start until 1952. The London ones were all built by 1953 but the others took longer and it was not until 1956 that the last, at Shirley in Birmingham, was completed.

1950’s War Rooms by Region:

- Newcastle: Kenton Bar

- Leeds

- Nottingham

- Cambridge

- London: 4 Sub-Regions: These sites are detailed in the feature ‘The London Civil Defence Controls’

- NW London: Partingdale Lane (Mill Hill)

- NE London: Wanstead

- SE London: Chislehurst (Kent)

- SW London: Cheam (Surrey)

- Reading

- Bristol

- Cardiff (Coryton)

- Birmingham (Shirley)

- Manchester

- Edinburgh: Eastern Zone War Room (Kirknewton). Western Zone War Room (East Kilbride)

- Tunbridge Wells

- Belfast

The Working Party considered the position in London in 1950. It was decided that the best place for the London Region War Room would be in the vicinity of Ken Wood in Hampstead which would be near both the army’s proposed wartime headquarters at Kneller Hall and close to a main GPO cable to link with the Central War Room. It would need a staff of 1500 with at least 100 on duty at any one time for operational purposes. However, it was not proposed to put the whole staff in one building but to disperse them locally perhaps in schools in a way reminiscent of the plan to disperse the central government operations to the North West suburbs before the start of World war ll. In fact, a London Regional War Room was never built. Instead, 4 Sub-Regional War Rooms were built for each of the zones, later called groups, which London was divided into for civil defence purposes. These were single storey versions of the standard Regional War Room design. A War Room for the whole of London may have been considered unnecessary given these Sub Regional ones. In any event, when Sub Regional Controls were introduced for the major conurbations in 1955 the London groups were redesignated as sub-regions and it was planned to locate their controls further away from the built up area of London. In addition, throughout the later years of the 1950s an idea was gaining acceptance that in war London should be divided between its neighbouring regions which would do away with any need for a London War Room. However, “Paddock”, the former Cabinet bunker in Dollis Hill was designated as the joint civil/military headquarters for London and it appears to have been used in a Regional War Room role during Exercise Dutch Treat in 1956.

The Regional War Rooms would report to a Central Government War Room (which was also at this time being called the Central War Room or the Civil defence Central War Room) in London. This would probably have taken on the information gathering and disseminating role that the Ministry of Home Security War Room had during the Second World War.

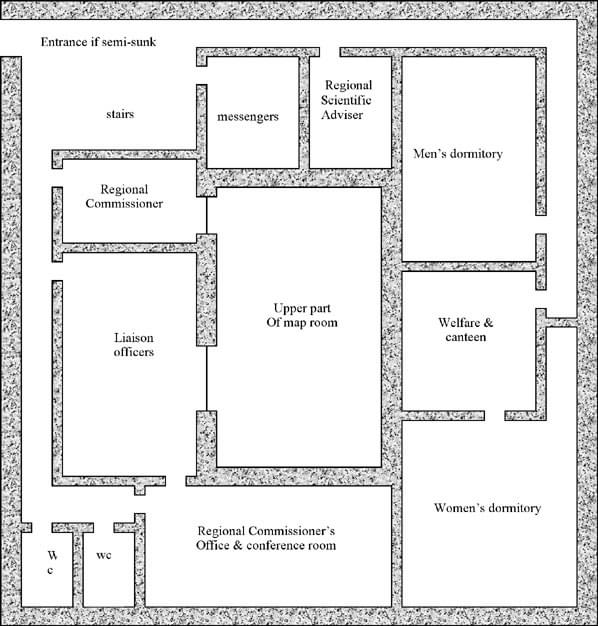

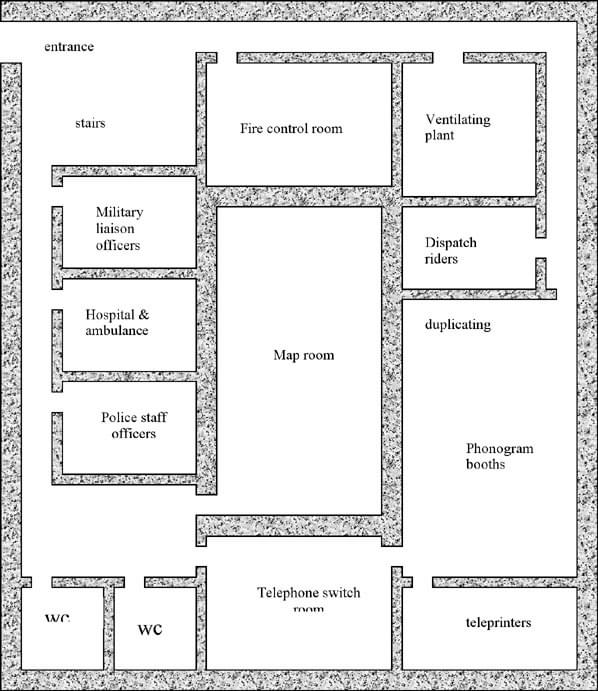

The Working Party drew up a model layout for a War Room with 5968 square feet of accommodation on 2 floors. Originally they said that existing buildings might be used and the model layout adapted to meet them but in practice completely new war rooms were built except in Newcastle where a World War ll bunker was adopted.

The model War Room was a 2 storey structure built either on the surface or with one level underground. It would have a reinforced concrete roof and walls 5 feet thick which would be proof against a direct hit by a 500lb MC type bomb. The new buildings were each expected to cost £36,720 to build, equivalent to about £900,000 in today’s prices. Additionally, the plant would cost £29,840 (£700,000). This was a huge expenditure for a country in a desperate economic position and shows the importance attached to civil defence at the time.

The war rooms were in practice based on the Working Party’s original structural designs and room layouts -

First Floor

Lower Floor

By the time building started fall-out had become recognised as a danger. As a result the ventilation and air filtration of the Regional War Rooms was greatly improved requiring a large single storey extension to one side of the War Room to house the new plant.

The allocation of rooms shows the role of the Regional War Rooms. They housed the Regional Commissioner (and his deputy) and his staff who would direct the strategic response to an air raid. The principal players would be the rescue services - the Civil Defence Corps, the fire and police services and the medical teams assisted if possible by the military. There would also be a few representatives of the government departments involved in civil defence. They would collect information about the attacks the region had suffered and direct operations at a strategic level. The response would be a short term one aimed at helping the survivors, clearing roads and other measures to cope with the immediate effects of the attacks.

At the heart of the War Room was a 2 storey operations and map room. Dominating this room and filling one wall was a regional map, made of metal so that magnetic symbols could be used. The rooms facing into the operations room on both levels had large windows so that the displays could be easily seen.

The War Room would have been helpless without an effective communications system and extensive telephone and telegraph facilities were included. Most plans included provision for motor cycle despatch riders and later plans included the use of radios.

It was expected that the War Rooms would have to be manned continuously and domestic facilities were provide and as it was thought that at least one shift might have to remain in the War Room during an air attack small dormitories were provided.

The operational staff for the War Room would have been provided by the Civil Defence Corps, the police, ambulance service and so on but they would also need a “common services” staff to run the map and operations room and man the communications facilities. These would have come from government departments with offices nearby but finding these people was a problem throughout the life of the War Rooms. Originally it was thought that 2 shifts would be sufficient but later a third was added to cover for sickness, etc. Each shift was to consist of 21 people manning the operations room and signals office but this later crept upwards especially when fall out reporting was added to the roles so that the shift increased to 37. Staff for these shifts was only recruited for peacetime exercise and training purposes and little thought seems to have been given to manning the War Rooms in an actual war. Even so volunteers were hard to come by and government departments were reluctant to release staff for training or to pay for overtime. Quite often during the even limited exercises Home Office staff or members of the Civil Defence Corps were drafted in to make up the numbers.

The original role of the War Rooms was given in early Civil Defence Corps training notes as -

- To report immediately to the Home Office War Room first bombs and flares and other vital information.

- To arrange assistance for towns under attack (eg from other towns and Regional Columns).

- To collate information, send situation reports and disseminate essential information.

- To co-ordinate all operational movements

Operational instructions drawn up in 1953 expanded on this. They described the “Civil Defence War Room” as “a protected building designed to accommodate the Regional Commissioner and those members of his staff concerned with war time operations of the civil defence and fire services, and of the police”. The “main operational duties to be carried out in a Regional War Room” were -

- Receive and collect reports -

- on air raid damage and casualties occurring within the region

- of other important events which are important because of their effect on the prosecution of the war.

- Order the movement of reserves to areas which have suffered damage or casualties beyond the scope of their local resources.

- When the situation demands such measures -

- call for assistance from other fighting services, or

- ask the Civil Defence Central War Room to send reinforcements from other regions.

- Supply the Civil Defence Central War Room with regular situation reports.

- Ensure, by means of a general oversight of the conduct of operations within the region, that available resources are deployed to the best advantage.

- Liaise with and make essential information available to the fighting services, the regional headquarters of government departments and all authorities concerned with any aspect of civil defence.

- Circulate to those concerned information regarding the enemy’s tactics, the types of weapons in use by the enemy and their probable influence on operations

At this time it was assumed that the next war would follow the pattern of the last with conventional air raids spread over an indefinite period. However, by the time construction of the War Rooms was under way the Soviet Union had acquired atomic weapons. It was now assumed that there would still be many months of warning in which to prepare for a war so there was no need to rush the plans forward but when war came it would open with what the 1953 Hall Report called “a period of unparalleled intensity”. The UK would be subjected to very heavy atomic and conventional air attack and could expect to be hit with between 100 and 200 (134 were actually used for planning purposes) atomic bombs of the Hiroshima type (i.e up to 20 kilotons) directed at London, the major ports, centres of population and industry and atomic air bases. During the Second World War the Regional Commissioners had been empowered to assume the full powers of the central government to rule in their regions if contact with London were lost because of destruction, complete loss of communications or invasion. This idea was retained in the early plans but the Hall Report envisaged that the Regional Commissioner would now inevitably be needed to “take over the reins of Government from the shattered central administration”.

By 1955 the Strath report was predicting that the arrival of the hydrogen bomb would signal the end of this type of warfare and that the next war would last a matter of hours at the end of which the country would be wrecked and covered with a blanket of fall out. Previous ideas of civil defence would be largely irrelevant and all resources would now have to be directed to the “struggle for survival” directed by the Regional Commissioners with, possibly, some direction from the embunkered central government nucleus at Corsham.

The new ideas about World War 3 lead to the Regional War Rooms being given a role in fall out monitoring and they would receive reports from the Royal Observer Corps Sectors and from people on the ground. The Strath Report however would have a greater impact. It suggested the need for the strengthening of the regional organisation and this was developed by the Padmore Committee looking at central government in war. This lead to the idea that after an attack with hydrogen bombs the central government in London would cease to be effective and the Regional Commissioners would have to take over. This would mean that they would have to be given much larger staffs with representatives of all the “due functioning” government departments. The military would also have a much greater role. This lead to the idea of the ‘joint civil/military headquarters’ which would evolve, in the early 1960s into the Regional Seats of Government. The new headquarters would have a staff of 450 compared to less than 100 in the Regional War Rooms. They would also be operating for longer. The existing Regional War Rooms would be far too small and plans were drawn up for new, purpose built headquarters. At the heart of the new headquarters would be a central operations and intelligence room which would be a reinforced ‘central redoubt’ with a protection factor of 1000. This would in effect be the new War Room through which the Regional Commissioner would exercise his operational functions in war. It would be the heart of the new headquarters and direct the region through the survival stage following the attack. Once the survival stage moved into the recovery stage the emphasis would switch from dealing with the effects of the attack to governing the region for the long term. The War Room would then move away from an operational role to more of an intelligence and secretariat one.

The new headquarters were never to be built but in 1957 ad hoc plans were drawn up to base the joint civil military headquarters in existing buildings including, possibly where there was additional accommodation close by, some of the existing Regional War Rooms. Exercises were held during the second half of the 1950s using the Regional War Rooms but these were essentially to test the passing of fall-out information with the civil defence role proper not being tested. Very little was done to plan for the joint civil/military headquarters and by the early 1960s they had been redesignated as Regional Seats of Government. The redesignation demonstrated a further move away from the idea that the regional headquarters would be responsible for directing the rescue effort in the immediate aftermath of the attack. From now on this would be done by sub-regional and local authority controls leaving the RSG to plan strategy. This effectively meant the end of the Regional War Rooms' role although some of the original buildings such as Cambridge and Nottingham were enlarged to become RSGs and others such as Leeds and Tunbridge Wells were kept as the communications centres for split-site RSGs.