Struggle for Survival

Governing Britain after the Bomb

The 1955 Defence White Paper said that a future war would result in a “struggle for survival of the grimmest kind”. This book examines the way in which the government in Britain prepared for that struggle during the Cold War and the work done, often in complete secrecy by the civil and home defence planners at all levels.

Contents

- File 1: The Death of Bristol The effects of nuclear war - the civil defence response

- File 2: Any Measure Not Amounting to Actual Combat What is Civil and Home Defence? - lessons from World War II - The Civil Defence Corps - Central Government and Regional War Rooms

- File 3: A Difference in Kind - The Megaton Weapon Central Government in War - the Strath Report - response to the H bomb

- File 4: The Central Government Nucleus SUBTERFUGE, BURLINGTON, TURNSTILE, etc - Protecting the Queen

- File 5: The Regional Seats of Government The what’s, where’s and how’s of the RSGs

- File 6: Regional Government Sub Regional Controls - the end of the RSGs and the Corps

- File 7: From Civil Defence to Emergency Planning New strategies for the 1970s and 1980s - Protect and Survive - Exercise Hard Rock - new roles for local authorities

- File 8: Rethinking Regional Government Changes at regional level - Exercise Regenerate

- File 9: Central Government in War in the 1980s Conventional war - COBRA and PINDAR

- File 10: Emergency Laws New laws for wartime

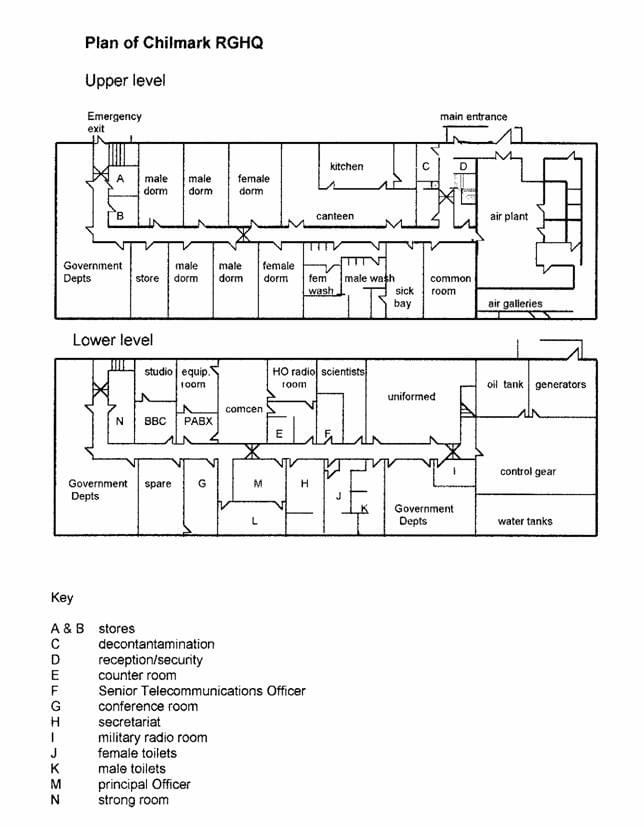

- File 11: The Regional Government Headquarters RGHQs - history - sites and organisation - Chilmark in detail

- File 12: The Role of Local Authorities in War Controllers - Regulations - plans - emergency centres

- File 13: The Ministries Prepare for War Departmental plans - the War Book - health - transport - energy

- File 14: Feeding the Survivors Rationing - stockpiles - emergency cooking

- File 15: The Uniformed Services Armed forces - fire service - police

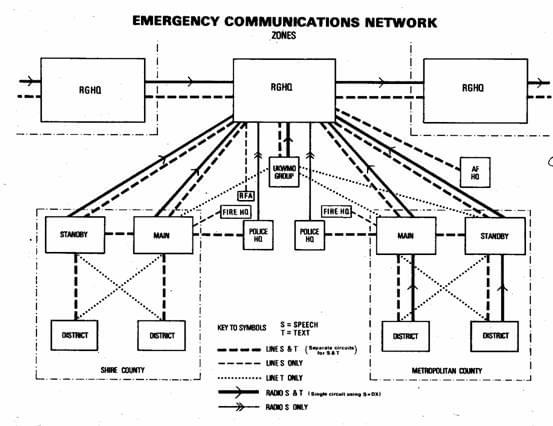

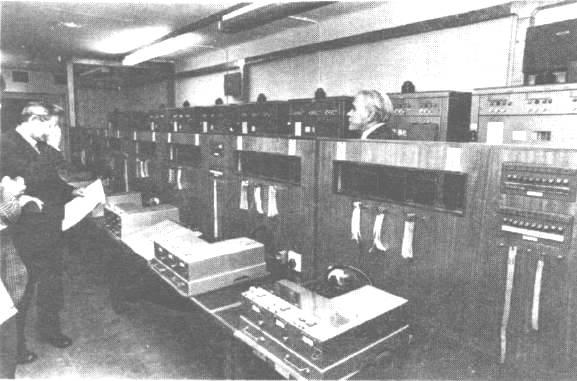

- File 16: Civil Defence Communications and Warning Wartime broadcasting - emergency communications - attack warning - Royal Observer Corps

- File 17: The Road to War Countdown to the attack - the aftermath

- Appendices

File 1: The Death of Bristol

The effects of nuclear war - the civil defence response

The morning of 8 March 1966 dawned clear and bright. The few high clouds promised a sunny day, perhaps the start of an early spring. As the people of the small Gloucestershire village of Almondsbury started on their daily tasks many worried about the worsening political situation in Europe. But even while armies prepared for war village life had to go on - children went to school, groceries were delivered, cattle were milked. No one noticed the small dark speck high above them in the morning sky.

The Tu-95 bomber of the Soviet Air Force had taken off from its base in northern Russia 10 hours before. It crew were tired and frightened as the bomb aimer counted down the seconds to release. Suddenly, the huge aircraft jumped upwards now freed of the massive weight of its single hydrogen bomb. A short 45 seconds later the radio altimeter triggered the fusing mechanism and the bomb exploded with the force of 2 million tons of high explosive 5000 feet above the village church of St Mary’s. Almondsbury ceased to exist.

The village and its people were instantly vaporised leaving a crater 2000 feet across and 150 feet deep. People 5 miles away in Bristol, the bomber’s intended target, seeing the flash from the bomb hundreds of times brighter than the sun were blinded before they were struck by waves of searing heat and deafening noise from the blast. A minute later the blast wave arrived smashing buildings, throwing vehicles into the air and turning windows into blizzards of deadly glass that ripped though anything and anyone in its path. Even at this distance over 6000 fires were started in north Bristol. Fed by broken gas mains, the fires overwhelmed the fire services and merged into a conflagration that turned into a firestorm. In a matter of hours most buildings were destroyed and 80000 people were dead. Thousands of others were severely injured by burns, blast and flying glass or paralysed by shock.

But Bristol was not alone. Over the next two days hundreds of cities throughout Britain, Europe, North America and the Soviet Union shared its fate as World War 3 began and ended in a deluge of hydrogen bombs. Six more bombs hit Southwest England with a total explosive power of 13 million tons of high explosive. Over 450000 died. Thousands more would die over the coming weeks from the effects of radioactive fall out, untreated injuries, disease, riots and starvation.

The attack of course never happened. It was part of the background scenario for Exercise Grass Seed prepared by civil defence planners in 1966 to examine the problems of survival in Southwest England after a major nuclear attack. The scenario revealed the horrors and scale of the nuclear war the planners expected and tried to prepare for.

Although the planned official evacuation scheme had not started, over 100000 people had left Bristol before the attack. They joined over 3 million refugees from the Midlands and Southeast fleeing to the perceived safety of the Southwest. Every hotel and guesthouse had quickly filled and thousands were living in temporary accommodation in schools and factories. But many others were living rough in the open where they were caught by blast and fall out.

The desperate position of many refugees added to a rapid break down in law and order even before the attack. By D+7, 7 days after the attack the situation had reached crisis point as desperate people with little hope and faced with a total collapse of society behaved like savages. Householders were increasingly reluctant to take in refugees. Small towns and villages were particularly badly pressed and many formed armed vigilante squads refusing to allow anyone in or any supplies out. In the face of widespread looting and attacks on food supplies the Regional Commissioner exercised his unfettered legal authority and ordered drastic measures including public floggings and executions. The overstretched police and armed forces had to be withdrawn from many areas and were formed into a “striking force” which took on the worst areas of anarchy, using tanks to break down barricades. By D+20 law and order had been re-established in most areas but it existence was fragile.

Bristol was largely unaffected by radioactive fall-out thanks to favourable winds but elsewhere it proved deadly. Drifting on the wind, it silently and slowly killed thousands. There was no cure and the over-stretched medical workers were ordered not to waste their efforts on its doomed victims. The worst affected areas were called Z-Zones where the survivors had to stay under cover until rescued but many Civil Defence volunteers quickly exceeded their War Emergency Dose of radiation and soon all rescue efforts were withdrawn from the Z-Zones. In the region an estimated 85000 people were abandoned to die.

The Regional Commissioner ordered Bristol north of the River Avon and anyone still alive there to be abandoned. To the south of the river most of the injured found some form of medical facility although this was often primitive and with supplies and staff exhausted by D+20 treatment was virtually non-existent. People died in their hundreds. Mass graves were dug in hospital grounds and parks where the bodies of humans and animals were dumped without ceremony. There was no prospect of burying the tens of thousands trapped in smashed houses and in many places the dead rotted where they had fallen. The risk of disease was a major concern for the authorities but they were powerless to prevent it.

All roads to the north of the river were blocked by debris and wrecked vehicles. By D+20, the main roads were open from Bristol to the south and west but further road clearance work was stopped to preserve fuel and equipment. The public utilities were virtually wiped out by the attack. South Bristol had some supply of gas coming from Bath but its own gas production facilities were smashed. The entire region was without electricity and no generating stations were expected to be operating for at least 2 months. Supplies of petrol and diesel were short. There was no refining and many underground storage tanks were effectively sealed by the lack of electricity for pumping. As with all other supplies there would be no prospect of obtaining anything from outside the region for months, if not years. The police and armed forces were given priority with fuel for law and order work, followed by medical, welfare, public utilities and food distribution but some fuel had to be preserved for agricultural use in the future. Bristol still had some piped water supply although the quality was low and the sewage system was inoperative and likely to remain so for months. This would only add to health problems in the coming weeks and months.

The public telephone and telegraph service was non-existent and only civil defence controls had some very limited communications. Radio broadcasting was limited to a daily 5 minute bulletin from the Regional Commissioner giving news and encouragement but few people had battery-powered radios so most did not hear him. Attempts were made to set up local newssheets but there were no printing facilities in Bristol. In the absence of news rumours fed people’s fears.

Food was not an immediate problem. By D+20, most survivors in Bristol were being fed at outdoor emergency feeding centres. There were ample supplies of meat but a shortage of vegetables. Flour would last a few more days but bakeries and flourmills were unable to operate because of shortages of fuel and water. Salt supplies were exhausted and stocks held at council road depots to de-ice roads were being used. Consideration was being given to using pet food for human consumption. The feeding centres were however running short of fuel and with the poor weather, some were becoming unusable. Food poisoning was common in the unhygienic conditions.

Few people went to their peacetime jobs. There were attempts to enrol all able bodied survivors to do manual labour, help in food preparation, hospitals, etc but many were reluctant to move from their homes. The Regional Commissioner tried to keep the economy going by insisting that people paid for food but this proved unworkable and had to be abandoned.

Overall, although the survivors in Bristol were in a better condition than many others in the region their position was precarious. Theirs was a battle for simple survival from day to day. The old, the sick, the injured and the very young were doomed. There was little thought for the future. Many would not live to see it.

This was the horror of a full-scale nuclear attack in the age of what the strategists called Mutually Assured Destruction or MAD when they assumed that the next world war would start and end with an immediate all-out exchange of city-killing hydrogen bombs. The immediate effects were on a scale never before imagined but the long-term effects of radioactive fallout made matters worse. The combined effects would virtually destroy all vestiges of civilised life even in areas not directly affected by the explosions.

These are the events that civil defence planners prepared for during the Cold War. This book describes those plans.

File 2: Any Measure Not Amounting to Actual Combat

What is Civil and Home Defence? - lessons from World War II - The Civil Defence Corps - Central Government and Regional War Rooms

Home and Civil Defence

Films of the London Blitz show fire crews in action, rescue parties digging for survivors, ambulances taking the injured to hospital and smiling ladies dispensing tea and sympathy. This is most people’s idea of civil defence. But the civil defence plans that evolved before and during World War 2 went beyond this to cover all aspects of what is called passive defence. This included pre-attack preparations such as evacuation, black out and shelters, then the wider activities of the emergency and rescue services and later the longer term response with emergency feeding, billeting and rebuilding.

The Civil Defence Act passed in 1948 defined civil defence in these wider terms as “including any measure not amounting to actual combat for affording defence against any form of hostile attack by a foreign power or for depriving any form of attack by a foreign power of the whole or part of its effect, whether the measures are taken before, at or after the time of the attack”. Some 10 years later Civil Defence Corps training material was repeating this wider approach saying that civil defence was “that part of the defence of the country organised to mitigate the effect of the attack, as distinct from military action to combat the attack itself.”

The Emergency Planning Guidelines for Local Authorities published by the Home Office in 1985 which is discussed at length later repeated this basic idea when it gave the priorities for civil defence as -

- Providing protection against the immediate effects of conventional and nuclear weapons

- Ensuring the maximum use of the precautions that could save large numbers of people from the effects of radiation.

- In planning to meet the shortages and disruption which would follow war.

- In planning for the restoration of essential supplies and services

- In setting the groundwork and organisation that would help promote recovery.

This list suggests that civil defence is about caring for people. But the government looks beyond these immediate activities to systems of administration, organisation and control from the local level right up to central government. In civil defence terms these levels form a chain of command and as we move up through the levels the emphasis changes from looking after people to looking after institutions. At the top, at the level of the central government the emphasis is on preserving the basic institutions of the state and ensuring they can continue to function. In the United States, this is referred to as the “continuity of government” but in Britain, it is called more bluntly “the machinery of government in war”.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the plans for responding to a nuclear attack steadily moved away from the idea of civil defence as the immediate life-saving response to an air raid to one where the priority was the protection and preservation of national institutions and in particular the apparatus of government. By the end of the 1960s planners were also thinking about problems which might arise in the period before such an attack. This lead to the wider concept of “home defence” which was defined as -

“Those defensive measures necessary in the United Kingdom: -

- to secure the United Kingdom against any internal threat;

- to mitigate as far as is practicable the effects of any direct attack on the United Kingdom involving the use of conventional, nuclear, biological or chemical weapons;

- to provide alternative machinery of government at all levels to increase the prospects of and to direct national survival; and

- to enhance the basis for national recovery in the post-attack period."1

This definition formed the basis of civil defence planning until the early 1990s. The first measure concerns the military’s, and to a lesser extent the police’s role in defending the state and its people against subversion, sabotage and terrorism not just in a wartime context but also in a period of civil unrest. The second measure deals with what most people consider to be civil defence but the last two measures go beyond this. In many ways the story of British civil defence during the Cold War is the story of the move away from the second measure to the third. The movement away from looking after people to looking after institutions; from the short term to the long term.

Lessons from World War II

When planners started to consider civil defence for the Cold War, they looked back to the experiences of the Second World War that had ended only three years before when the extensive civil defence measures had generally worked well. The key elements of civil defence for the next forty years were based on these measures and it is appropriate to start an examination of post-war civil defence with an overview of what went before it.

During the 1926 General Strike England and Wales were divided into 11 areas each under a Civil Commissioner who was given special powers for ensuring that food supplies and other essential services were maintained. In the 1930s when plans were laid down to deal with the effects of the air attacks that were expected to lay waste to the cities in the war that loomed ever closer Civil Defence Emergency Scheme Y built on this structure. The Civil Commissioners would now be called Regional Commissioners and the areas became Regions. As it would be the main target, London now became a region in its own right and the remainder of South East Region was given the number 12. These boundaries for the civil defence regions would remain largely unchanged for the next 50 years. The Regional Commissioners, who were men of influence and standing rather than politicians, each had a War Room with a staff of civil servants. Their primary task was to oversee the civil defence effort in their regions but at the operational level the organisation of the Air Raid Prevention or ARP forces, the fire services and health workers was the responsibility of the local authorities.

The Regional Commissioners also had a secondary and potentially more important function. In the event of the central government in London being unable to exercise control throughout the country (which effectively meant the Regional Commissioner losing contact with the Ministry of Home Security War Room), the Regional Commissioners could, at their discretion, assume full powers of civil government in their region.

While the ARP organisation headed by the Regional Commissioners would look after the local situation, the government had to ensure that its own operations, which were then firmly based on central London, could continue throughout sustained air attacks and even an invasion. These “machinery of government in war” activities would cover many levels of the governmental and administrative machine. At the top was the decision making apparatus centred on the War Cabinet with the heads of the armed forces and their advisors. Below them, at national level would be the various layers of the civil service together with quasi-governmental bodies like the BBC, General Post Office, British Railways, etc who would implement and add to those decisions. Consideration would also need to be given to the continued operation of the monarchy and Parliament. Probably around 150000 people fell into these categories and this number would rise steadily during the war as the role of the government expanded.

The initial plan was to relocate the core of the machinery of government to the suburbs of north and northwest London. The War Cabinet would use a bombproof citadel known as PADDOCK2 at Dollis Hill with supporting bunkers at Cricklewood and Harrow. PADDOCK was built 40 feet underground and had some 22 rooms centred on a Map Room. The bulk of the supporting civil servants would be accommodated in neighbouring schools and colleges left empty by evacuation.

But before the war started, the plan was changed. Now, the core or seat of government would remain in London for as long as possible and protected accommodation was developed for it. The most famous was the bunker under the New Public Buildings that was partly occupied by the Central War Room, later to became known as the Cabinet War Room. Work had begun on this in 1938 by reinforcing the building’s basement and equipping it with air conditioning, communications gear and some basic domestic facilities. It could house 400 staff and its activities centred on the Map Room, which collected information relating to the war effort and collated daily reports.

The functions of the Cabinet War Room, according to a contemporary file, were -

- To maintain an up to date picture of the war in all parts of the world for the information of the War Cabinet and Chiefs of Staff,

- To provide a channel for communicating very important military news to HM the King and members of the War Cabinet through members of the War Cabinet Office,

- To provide a protected meeting place for the War Cabinet and the Chiefs of Staff organisation under air raid conditions.

There were four other principal war rooms - three for the fighting services and one for the Ministry of Home Security. By 1942 all had found permanent homes. The War Office occupied a new bunker built on the site of Montague House between Whitehall and the Thames. The Admiralty also had a new blockhouse, usually known as the Citadel, which was in fact built illegally on part of St James’s Park adjacent to its main building. The Air Ministry and Ministry of Home Security War Rooms were installed in a site known as the Rotundas. This complex located in Horseferry Road near Whitehall used the enormous holes dug for the gasholders of the Gas Light and Coke Company for its 2 principal bunkers. In January 1946 The Times reported that the 3-storey deep Rotundas, then codenamed ANSON, could have housed the War Cabinet, the Chiefs of Staff and 2000 staff in the event of “mass bombing or enemy landings dislocating or destroying the usual centres of administration”. The report added, interestingly in view of later developments, that its 12 feet thick “concrete crust was believed by experts to be proof against an A bomb”.

The Ministry of Home Security had been conceived in 1935 to combine responsibility for air raid and fire precautions and to co-ordinate the war time services of all other civil departments. It was originally part of the Home Office which provided its staff. However, its functions and responsibilities grew rapidly and by 1942 it was employing 5700 people. Its War Room was central to its operations and indeed to all civil defence operations throughout the country. Its functions were given as -

- To receive reports of first flares and bombs,

- To receive and action requests for assistance from the Regions,

- To act as a channel of communications between the regions and their Commissioners and the Government,

- To act as an intelligence centre to present a picture of the Home front,

- To prepare situation reports.

The Regional Commissioners were provided with their own war rooms in provincial cities such as Cambridge and Manchester usually using reinforced basements of large houses. These Regional War Rooms would co-ordinate civil defence activity in the region and act as the government for the region if communications with the Ministry of Home Security War Room were lost.

As well as these citadels for the principal War Rooms a series of reinforced “steel framed buildings” which were expected to be able to withstand blast better than ones built of brick or stone were constructed in central London to provide office accommodation for the various government departments.

The War Rooms were the core of the seat of government and were linked by a communications tunnel running 100 feet beneath Whitehall. This was not intended for people but to protect the vital telephone and telegraph cables. The tunnel, which was completed in 1941, was 12 feet wide with narrower tunnels carrying the cables into the War Rooms. Soon after, it was extended to connect with the Rotundas. Early in the war another tunnel 25 feet wide to run parallel with the cable tunnel to provide war room accommodation was considered but never built.

As well as planning protected accommodation for the core or seat of government plans were developed by the start of the war to move civil servants from central London in what were known as the Yellow and Black Moves. The Yellow Move planned to relocate some 44000 civil servants with less important administrative jobs permanently out of London mainly to the north of England and Wales. The Black Move envisaged moving the 16000 civil servants, military personnel and others who formed the actual Seat of Government to various locations in the west Midlands. The War Cabinet would use Hindlip Hall whilst the Prime Minister, his Private Office and family would go to Spetchley Hall. At the same time, the Royal Family would have moved to Madresfield Court. These stately homes are all near Worcester. Parliament would have sat in Stratford-upon-Avon. The 5 War Rooms would have been set up in requisitioned hotels and schools in Cheltenham. The idea was that both the Yellow and Black moves could be completed if necessary in 3 - 4 days but in practice only some 20000 civil servants actually moved over several weeks and even this caused tremendous practical problems.

The practical problems revealed by the limited Yellow Move, the generally bad experiences of the French government’s move from Paris in the face of the German advances and the fact that much of the planned relocation areas were now within range of German bombers led to the Black Move being abandoned in mid-1940 but it was reconsidered in 1943 in the face of bombardment from what would become the V-weapons. By this time, there was sufficient “citadel” (purpose built bunkers) and “fortress” (steel framed buildings) accommodation to accommodate around 10000 key personnel in central London under what were called “Crossbow Conditions”. If the bombardment became severe and prolonged non-essential government workers would be stood down whilst the nucleus would live and work in the citadels and basements. The Cabinet War Room would still be the hub.

However, doubts had always existed about the ability of the Cabinet War Room to withstand a direct hit and when planning started for the German V-weapons alternative accommodation was provided for Churchill, his family, the Cabinet and the Chiefs of Staff in the Rotundas. These were considered proof against a direct hit from a 1000lb bomb and the safest accommodation available. However, only domestic accommodation was provided. The War Rooms continued to operate in their existing premises.

In 1945, the Air Raid Precautions organisation, which had steadily become more commonly become known as civil defence during the war, was totally dismantled. The euphoria of VE Day and VJ Day was however short lived. In 1946, Churchill first spoke of “the iron curtain” and in the following year the term Cold War was coined. Only two years later, to the shock of many in the West the USSR exploded its first atomic bomb. Civil defence suddenly became a necessity again and the planners looked back to the last war for ideas both for bringing immediate assistance for the survivors of air attack and for a wartime system of civilian command and control.

The new measures were lead by the Civil Defence Act 19483. This was essentially an enabling provision that would allow the “Designated Minister”, which meant any Minister as may be designated by Order in Council or, in practice, where no Minister was specified, the Home Secretary, “to take such steps as appear to him from time to time to be necessary or expedient for civil defence purposes”. The Minister could impose these steps without the approval of Parliament by issuing Regulations made under Order in Council. In particular, the Act made specific reference to power to issue Regulations to local authorities and police forces concerning the provision of civil defence measures. If an authority refused to comply, the Home Office could take steps to enforce the regulations. This happened in a few places, for example in 1954 Coventry City Council refused to have anything to do with civil defence which lead to the Home Office appointing 3 Commissioners to carry out the council’s duties. The Act also allowed Regulations to be issued to the public utilities (then nationalised, or soon to be nationalised) such as the power and water companies requiring them to make active civil defence preparations. Many Regulations quickly followed the passing of the Act such as The Civil Defence (Appropriation of Land and Buildings) Regulations 1952, The Civil Defence (Gas Undertakers) Regulations 1954, The Civil Defence (Hospital Services) Regulations 1949 and The Civil Defence (Transport) Regulations 1954.

There was no need for the Act to deal with measures to be taken at central government level as these could be made under existing common law or the prerogative powers and responsibilities of the Crown.

One of the first and most important actions was the introduction of The Civil Defence (Public Protection) Regulations 1949. These made county and county borough councils responsible for -

- Collecting and distributing intelligence about the attack

- Controlling and co-ordinating action necessary as a result of the attack

- Rescue

- Protection against “the toxic effects of atomic, biological and chemical warfare”.

- Advising the public on the effects of attack and protective measures to take

In addition local authorities would have to organise evacuation and reception, care of the homeless, information centres, disposal of the dead, emergency water supplies and so on

But more importantly, the local authorities would have to organise the new Civil Defence Corps that was to be the key element in the civil defence plans. Initially, it was suggested that the Corps should be a branch of the armed forces organised on similar lines to the army reserves. But this idea was soon dropped although there were some attempts during the 1950s to promote the Corps as “The Fourth Arm” alongside the 3 armed services. Instead, the Corps was established as a civilian body administered by the local authorities similar to the Air Raid Precautions organisation in the last war. This method of organisation is in contrast to many other countries where civil defence was a police or military function. There were also suggestions at this time that a Minister of Civil Defence should be appointed. This was not implemented although in 1953 the Queen “graciously accepted the title of Head of the Civil Defence Corps”. The civil servants who arranged this however dismissed the idea of incorporating the word “Royal” in the Corps' title.

The Corps would provide the basic organisation and staff for local authorities to comply with the newly imposed civil defence functions. It was to consist of Divisions of unpaid but uniformed volunteers enrolled by “Corps Authorities” i.e. the County Councils and County Borough Councils and organised by them. However, overall policy and conditions for the Corps were to be determined by the Home Secretary who announced them in a series of Civil Defence Circulars (or CDCs) to the Authorities. Recruiting for the Corps, the Auxiliary Fire Service and the National Hospital Reserve Service started in late 1949. A copy of the Warrant for the Corps is shown below.

Corps members were trained locally in rescue, first aid and so on by qualified instructors most of whom had been to one of the civil defence schools which were set up in 1956 at Falfield, Easingwold and Tayworth Castle. There was also a Civil Defence Corps Staff College at Sunningdale. But Corps members had no obligation to attend training sessions and they could leave the Corps at any time. They also had no obligation to serve in wartime.

The Organisation of the Civil Defence Corps

For operational purposes, the local Divisions provided by the Corps Authorities would join together into Areas and then Groups. The Group Controller would work under the direction of the Regional Commissioner at the Regional War Room. In this way in the South West Civil Defence Region (Region 7), 76 Group was made up from the Civil Defence Corps Divisions of Devon and Exeter and was split into 5 Areas. The County Borough of Plymouth together with parts of Devon and Cornwall formed 77 Group.

Each of the 400 or so Groups and Areas in England and Wales together with the 70 in Scotland would require its own control centre. The Home Office had given some suggestions about setting up these controls in the early 1950s. These reflected practices from the last war. Controls were to be set up depending on the size of the local population and would normally be away from potential targets such as railway yards and factory complexes. Their role would be, as one report put it “…a communications and intelligence centre at which the controller and his staff will operate during the mobilisation and life saving periods, and if necessary into the survival period”. They would not be used continually and would not need anything other than basic domestic facilities. Whilst many authorities re-used Second World War controls and many new ones were opened a large number of authorities lacked credible control premises. Some more detailed guidance about setting up a control was given to corps authorities in 1961 but due to a lack of funds these would normally be set up in existing premises. A Group Control could have some 3950 sq. ft of usable space and an Area Control 3350. Nominally, they would have staffs of 48 and 30 respectively and both were to be self-sufficient for 21 days. The diagram below shows the purpose-built control built in Wellingborough in 1962 at a cost of £48242. The control was built in the basement of a new fire and ambulance station and has a floor area of some 3300 square feet.

Each Division of the Corps was divided into operational sections reflecting the Corps’s role in responding to the immediate effects of the attack at the local level -

Headquarters Section

This Section’s main function was to man the static and mobile controls at the various local levels of the control chain, to provide communications, to undertake reconnaissance and to provide scientific advice to Controllers. For this latter role specialist Scientific Intelligence Officers were recruited from local people with a scientific background.

Warden Section

A 1960s Corps recruiting leaflet described the Warden as “…the vital link between the individual and the mobile services. In a nuclear war he would become the leader of his neighbourhood, advising and controlling the public and seeing that the survivors get help and attention”. Wardens would be responsible for local reconnaissance and reporting, for the organisation of street parties and the deployment of life-saving services within their areas. They also had special responsibilities in connection with warnings of deadly radioactive fall-out produced by nuclear explosions and control of the public in areas affected by it.

Welfare Section

The members of this section would help the Wardens with any “dispersal of priority classes” as the formal evacuation scheme was called. After the attack, they would provide immediate help with food and shelter and in the longer term with organising community life.

Evacuation was to be an official policy until the early 1960s and the 1956 Defence White Paper said it was the cornerstone of civil defence. The proposed evacuation schemes show the scale of civil defence planning but also perhaps the naivety of some of those plans. The basic plan was changed several times but in the mid-1950s the intention was to evacuate virtually all children and their mothers, together with the elderly and the disabled from the major cities that were expected to be the main targets. This would involve moving over 10 million people in England and Wales and a further 1 million in Scotland partly by road but mainly by train4. This should be done in 7 days - 1 for planning and 6 for the actual movements. The evacuees would be billeted for an indefinite period with families in the Reception Areas that would mainly be rural towns and villages. The married men back in the cities would be expected to carry on as with “business as normal”, without their wives and children, while waiting for the bomb to drop5. At the same time as this mass evacuation was taking place over a million members of the armed forces would be on the move together with all their stores and equipment. Vast amounts of food and other strategic materials would be moved from the ports and 360000 hospital patients would be relocated together with 68 million cubic feet of hospital equipment.

After the attack the welfare section would be expected to find accommodation for any homeless survivors or refugees in rest centres and organise emergency feeding. In the absence of electricity and gas, and the lack of food in the shops most people would have to be fed in this way. For this purpose virtually every school in the country was designated as a rest centre or emergency-feeding centre. Accommodation Registers were held centrally to ensure that the different agencies from central and local government, the armed services, government ministries, etc did not intend to requisition the same premises. The owners of these earmarked premises were usually not told of the intention.

The Welfare Section would be assisted by voluntary organisations particularly the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service, which had been established in the 1930s specifically for an Air Raid Precautions role. The WRVS was active in civil defence during the 1950s and 1960s and it was specifically excluded from the effects of “care and maintenance” in 1968 when the Corps was abolished and its role later expanded into many areas of emergency planning.

Rescue Section

This section would provide units for rescue, giving first aid to casualties, debris clearance and emergency demolition work. They would be working alongside the regular fire service, members of the armed forces, particularly the RAF, and members of the volunteer Auxiliary Fire Service who were trained in home defence fire fighting. At first the rescue section was based on the heavy rescue squads of the last war and equipped with complicated heavy lifting and rescue gear but the scale of damage from an H-bomb meant there would simply be too many injured and trapped to cope with and their role was scaled down and the squads re-equipped with only hand tools.

Ambulance and First Aid Section

Members of this section would provide the organisation for administering first aid to casualties, organising their evacuation to Forward Medical Aid Units and on to hospital. In war, it would merge with the peacetime ambulance service and work alongside the NHS, which would be augmented by the National Hospital Service Reserve. The NHRS would provide qualified nurses and nursing auxiliaries for the expanded hospital service.

The position in Essex

The Essex Civil Defence Corps plans from 1965 illustrate the extent of the planning and the manpower needs of the Corps according to its war establishment.

The Headquarters Section should have had about 800 members who would man the county control, 4 county sub-controls, 31 district controls and various mobile controls that would replace any of the static or permanent controls if they were destroyed.

The operational area for the Warden Section was the local authority district such as a town, which would be divided into one or more “sector posts”. These in turn would be sub-divided into 3 to 5 “warden posts” and reporting to each one of these would be 4 or 5 “patrol posts”. It was these patrol posts each manned by 2 wardens that would have the immediate role of collecting information and passing it up to the higher-level control. Public houses were frequently designated to be warden or patrol posts in wartime. Essex was divided into 55 sectors, 264 warden posts and 1024 patrol posts requiring 3135 volunteers. The war establishment of the Essex Welfare Section was about 5300. The Rescue Section was divided into 5 columns with a total of 2542 personnel. The Ambulance and First Aid Section would provide 8 columns totalling 2624 volunteers

In total, the planned war establishment of the Civil Defence Corps in Essex was about 15000. To this figure can be added the various voluntary groups, the Industrial Civil Defence Service, the National Hospital Service Reserve, the Royal Observer Corps and the police and fire services to give a total of about 20000 people. This would mean that some 2% of the total population of the county would be directly involved in civil defence.

But despite the best efforts of the planners, advertising campaigns and many dedicated members the Corps failed to generate significant public support particularly in the 1960s. Even in 1958, the Civil Defence Official Committee was expressing concern about apathy and shortage of equipment for civil defence. In 1959, the war establishment in England and Wales was some 800000 but there were only 335000 civil defence members and not all of these were active. By 1965, the Corps was only at some 25% of its war establishment. At the same time the Royal Observer Corps strength was 17000 against an establishment of 25000.

Organised in parallel with the Civil Defence Corps was the Industrial Civil Defence Service. This was founded in 1951 to organise civil defence activities at industrial premises particularly larger factories. The Industrial Civil Defence Companies were organised and equipped by individual businesses who did not receive financial assistance although they did benefit from tax relief on the costs. In 1966 there were about 106000 volunteers and instructors in the Service.

In the early 1950s, the Home Office set up a Mobile Civil Defence Column to experiment with the idea of moving a large body of civil defence personnel and their equipment to a city after it had been hit by an atom bomb. The column, which had some 180 personnel and was self-contained was disbanded in 1954 but the arrival of the hydrogen bomb meant there was a much greater need to reinforce the civil defence forces in the directly attacked areas with “a disciplined body under direct military control”. This lead to the setting up in 1955 of the Mobile Defence Corps which would be trained and equipped for fire fighting, rescue and ambulance duties. It would be manned by army and RAF reservists who would receive some basic training at the end of their period of national service. In wartime they would be called up to form 48 Mobile Defence Battalions each with around 600 men. But the end of national service meant that there would be insufficient reservists to man the Corps and it was disbanded in 1957. There was also an attempt in these years to re-establish the Home Guard but this received little public support and was soon abandoned.

The Central Government War Room

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the civil defence planners expected the next war would follow the same basic pattern as the last. There would be widespread conventional air attacks on cities and from the 1950s some of these would include atomic bombs and chemical weapons. Plans were made accordingly. In the late 1940s, a national survey was made of all available shelter space; plans for censorship and blackout were drawn up and millions of new civilian gas masks ordered. There was even a Working Party set up “to consider the civil defence arrangements for domestic animals and wild animals in captivity”. By the early 1950s, the assumption was that war would begin with an initial onslaught of atomic bombs after which both sides would recover and fight an extended “broken backed” war with whatever resources could be scraped together.

By 1955, plans were being made on the assumption that the UK would be hit by 132 atomic bombs targeted on seats of government, industry and population with London receiving 35 bombs. The planners based their calculations on what they called the “nominal bomb” with an explosive power or yield of 20 kilotons6, roughly equivalent to those dropped on Japan. They predicted that these bombs would kill 1680000 people and injure another 957000. Two-fifths of the country’s houses would be wrecked and half of the manufacturing industry would be destroyed or damaged. The loss of life, casualties and damage would be horrendous but based on experience from the Blitz and the attacks on German cities like Hamburg and Dresden the attacks would not result in the breakdown of society or the system of government. Consequently, civil defence measures were only needed to help the survivors in the immediate “life saving” period to cope with the immediate and localised effects on the attack.

The results of the attacks would need to be monitored both regionally and nationally. The World War ll regions were therefore re-instated again under Regional Commissioners with the same dual responsibilities. They would oversee civil defence operations and if necessary assume complete control of the region if communications were lost with the central government in London.

However, more grandiose plans were developed for the central government. When planning started for World War 3 in 1948 the first idea was that the core of the government machine would remain in London but up to 20000 civil servants would be evacuated to sites used during the last war such as Blenheim Palace, Colwyn Bay and Bletchley Park (the home of “enigma”). This move was not to protect the civil servants but to free accommodation for the expected expansion of government and the influx of allied military staffs and mirrored actual events in late 1940 when the Yellow Move had been re-introduced to free office space in London. By 1950, the plan had evolved and the Soviet Union had the atomic bomb. It was assumed that London would continue as the seat of government but as the bombing steadily destroyed buildings, blocked roads and disrupted communications it would become progressively unusable and perhaps completely so after 6 months. The bulk of the 150000 civil servant and staffs of key organisations would now progressively leave as conditions dictated. The key phrase in planning was now “due functioning” meaning that all essential aspects of government and indeed national life should be able to continue through the war and in particular survive enemy bombing. Many ministries made plans for their areas of responsibility. The electricity industry for example was particularly well prepared with a National Wartime Grid Control Centre built at Becca Hall near Leeds together with a reserve at Rothwell Haigh and 7 other regional emergency control centres. It also had several specially built warehouses containing reserve generating and transmission equipment.

Even though the bulk of the civil service would leave, the nucleus of government would for practical and morale reasons remain in London to control the government machine and conduct the war. The nucleus would consist of people essential to the war effort from the government, civil service and armed forces together with representatives from allied governments and bodies such as the Bank of England, Boards of Nationalised Industries, the Red Cross, TUC and major companies such as ICI. The planners thought this nucleus would need 7800 people but as it would have to operate from the same wartime citadels and steel framed buildings as before numbers were restricted to the 5800 these buildings could accommodate. Some additional accommodation was however becoming available. A new bunker near the wartime Montague House citadel was planned to have places for 1750 people by 1955. The Rotunda site was also being refurbished to take 950 people by 1954. There are also hints in the Public Record Office files of a “deep tunnelling scheme” planned at this time somewhere under London probably in the Whitehall area which was codenamed PIRATE. It would accommodate 800-1000 members of the nucleus together with a large communications centre but it appears to have been overtaken by later plans to evacuate the seat of government from London. At the same time, the armed forces planned to set up a combined war HQ at Northwood in north London.

There is no mention in the available documents from this time of a new Cabinet War Room. The original premises had simply been closed at the end of the war and it may originally have been intended to simply bring them back into use. The 1952 War Office War Book refers intriguingly to a “Central War Room or Map Room”, which would be opened on the instructions of the Secretary of the Cabinet and locates it under The New Public Offices in Whitehall, the former location of the Cabinet War Room.

In February 1953 The Times reported that as well as new Regional War Rooms a Central War Room would be established. But this was not to be a new Cabinet War Room. The Times said that “information from all departments with civil defence responsibilities would be collected and collated” in this Central War Room. This suggests a purely civil defence function and publicly available documents in the 1950s concentrated on this role for the Central War Room or Central Government War Room as it was more often called in official circulars. One of these documents, for example said “It is proposed that the Government will establish an operations and intelligence centre in which information affecting all departments with civil defence responsibilities would be collated and from which advice and information would be distributed and instructions on such matters as inter-regional reinforcement issued”.

In fact, lecture notes had been secretly issued to civil defence instructors in 1952 which said, “A CGWR (as the Central Government War Room was usually called) representing all Government Departments will be established with dual responsibilities -

- Control of civil defence operations : the overall co-ordination of civil defence operational arrangements and issuing of orders on matter such as inter-regional reinforcement.

- Civil administration : the dissemination of information and direction of matters affecting the protection of the population and property and the maintenance of law and order and implementation of emergency legislation.”

This is really a restatement of the roles given to the Ministry of Home Security War Room in 1939 and shows that the CGWR would have repeated its function although there was at this time no intention to set up a separate Ministry of Home Security and the CGWR was the responsibility of the Home Office.

By the mid-1950s a home for the CGWR had been found in the old North Rotunda bunker, which at this time housed the Air Raid Warning School. This may have provided a convenient cover to allow the site to be equipped with the necessary equipment and communications to monitor the effects of air raids. But, the Rotunda site may not have been considered a permanent solution because a 1957 Home Office report advised Ministers that “it would be unwise to establish in NAVE or any of the London citadels the CGWR”. During exercises in the late 1950s the CGWR role was usually simulated. For example during the large scale fall-out reporting exercise called Four Horsemen held in 1957 its role was taken by directing staff at the Birmingham Regional War Room. The CGWR’s role was soon to be absorbed into the much larger SUBTERFUGE emergency war headquarters complex but the Rotunda site was still used and in 1962 it was used as the communications centre for Exercise Fallex62 when it was codenamed CHAPLIN. During the exercise it was also used as the “exercise seat of government” which might suggest that the site was also earmarked for the central government or Cabinet War Room role. However, for “security purposes” the site was not manned by the civilian elements that would occupy it in a crisis. In the 1960s, the huge Marsham Street office block was built over the Rotundas for the civil service and there is some evidence that they continued to be used as at least a communications centre into the 1980s.

The Regional War Rooms

At the local level, the civil defence effort would need co-ordinating and the wartime regions were re-instated under the direction of a Regional Commissioner. The Regional Commissioner’s were now given purpose built War Rooms which according to the 1949 Working Party would be “established outside the central key area of its Regional town, it must also be located in an area where adequate signal communications can be provided to keep the War Room in touch with other civil and military headquarters in the region…and with the Central War Room in London.” In practice, they were built at the sites of the regional civil defence centres from the last war: -

| Region | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Northern | Newcastle |

| 2 | North Eastern | Leeds |

| 3 | North Midland | Nottingham |

| 4 | Eastern | Cambridge |

| 5 | London | see text below |

| 6 | Southern | Reading |

| 7 | South Western | Bristol |

| 8 | Wales | Cardiff |

| 9 | Midland | Birmingham |

| 10 | North Western | Manchester |

| 11 | Scotland | Kirknewton |

| 12 | South Eastern | Tunbridge Wells |

| Northern Ireland | Belfast |

Under the original scheme London was to have its War Room at Ken Wood in Hampstead. From there the Regional Commissioner would control the 4 zones that the city would be divided into. During the last war, the London Region War Room7 had a large staff and this was expected to be repeated with the London Regional Commissioner having a staff of around 1500 although only about 100 would be accommodated in the War Room. However, by 1951, this idea had changed and London was given 4 single-storey surface built war rooms, which were styled “sub regional commissioner’s war rooms” at Mill Hill, Wanstead Flats, Chiselhurst and Cheam.

The Scottish War Room or Scottish Central War Room as it was also styled would have 2 subordinate war rooms at Edinburgh and East Kilbride serving Scotland’s Eastern and Western Zones respectively.

The War Rooms were built to a standard design of a 2-storey building giving some 9500 square feet of space. They were all built on the surface although some had the lower floor below ground level. The roof and walls of the box like, windowless buildings were 5 feet thick and designed to withstand a direct hit from a 500-pound bomb. The rooms were arranged around a central 2-storey map room and the first floor offices were glass fronted so they could look down on the main regional map. In wartime, the Regional Commissioner would be supported in the War Room by an operational staff of scientists, communications operators, members of the Civil Defence Corps, the military, the emergency services (notably the fire service) and government ministries who could assist him with the strategic direction of the immediate civil defence effort during and after any attack. The war rooms were equipped with their own generator and air filters together with extensive communications equipment served by 40 staff working in shifts. Although not intended for continuous occupation they had small male and female dormitories equipped with 2-tier metal bunks, a few showers, a canteen and a small kitchen. The Regional Commissioner would be supported by a Deputy Regional Commissioner and one of his main roles would be to call Post Raid Conferences with representatives from central government, local authorities, the armed services and industry.

Reading Regional War Room in 1997 (Mark Bennett)

Building of the War Rooms did not start until 1952. The London ones were all built by 1953 but the others took longer and it was not until 1956 that the last, at Shirley in Birmingham, was completed. The War Rooms were soon over-taken by other plans but they continued to be exercised until around 1960/61 when the larger Regional Seats of Government started to become operational.

According to lecture notes given to Civil Defence Corps instructors the role of a regional war room was -

- To report immediately to the Home Office War Room first bombs and flares and other vital information.

- To arrange assistance for towns under attack (eg from other towns and Regional Columns).

- To collate information, send situation reports and disseminate essential information.

- To co-ordinate all operational movements.

If a city or town was badly affected an advanced headquarters would be set up on the outskirts to provide local co-ordination. In reality, these functions were little different to the Regional War Rooms set up during the Second World War and reflected the expectation that in the early 1950s the next war was expected to be fought, at least as far as the home front was concerned, on the same lines. From the mid-1950s the War Rooms were given the task of monitoring the new menace of fall out and their staffs were expanded so that they could operate continuously on a 3 shift basis. They were however to be overtaken by the consequences of the H bomb and their functions and operations were absorbed into the largely theoretical new joint civil military headquarters.

File 3: A Difference in Kind - The Megaton Weapon

Central Government in War - the Strath Report - response to the H bomb

The Padmore Working Party

In 1953 the Hall Committee was set up to consider the “national economy in war”. The Committee assumed that the central government would stay in London although the attack would kill many ministers and their officials. The Committee’s report questioned if the Regional Commissioner organisation could take over from them and highlighted the need for an effective central government in the post-attack period. The report lead to the setting up of a second committee under Hall to consider the economy during the “broken backed” period of the war and another under Maclean to consider the effect of atomic weapons on the armed forces. More importantly, a third committee was established under the chairmanship of Thomas Padmore, a Treasury official who had headed the Committee on the Redistribution of Government Staff in War since the late 1940s. This committee would consider the positioning of the seat of government during the initial stages of a future war.

Some information was becoming available from American tests about the effects of the new hydrogen bomb8 and the Padmore Committee took this into account. Its first recommendation, made in February 1954, was that the seat of government itself should remain in London using existing and extended “protective works” to accommodate 7700 key players. This would only deal with war fighting and foreign relations and other matters that needed to be centrally co-ordinated. As far as possible domestic government functions should physically be devolved to the regions. Padmore then wrote to government departments to ask what staff they would need to operate on a regional basis for the first fortnight of the war and the totals came to a surprisingly large figure of about 1000 in each region.

By this time new bunkers had been built in central London to supplement the original Second World War accommodation. By the early 1950s a new single storey bunker had been built roughly half way between the Rotundas and Whitehall under what is now the Queen Elizabeth ll Conference Centre. More significantly, the military had acquired a major new bunker in Whitehall Gardens near the site of the former Montague House. A building on this site had originally been planned in 1935 with a reinforced first floor and major air raid shelter basement. Part of this was completed and used during the war as the Montague House War Room. By 1954, a new bunker had been completed on the site 20 feet underground and topped with 9 feet of concrete to accommodate 700 people. A massive new building was then built for the civil service on the site which became the headquarters of the Ministry of Defence and is today usually known as “MoD Main Building”.

All these bunkers were linked to the Whitehall cable tunnel that was enlarged to provide underground pedestrian access to the various buildings. Additionally, a new tunnel was dug under Horseguards to provide a new telephone exchange. The General Post Office also expanded a wartime series of 7 feet wide tunnels under central London to carry cables between its main telephone and telegraph exchanges

At the same time, a major trunk exchange was secretly built in London under Kingsway alongside the Chancery Lane underground station by expanding one of the Deep Level Tube Tunnels built during the war as large-scale air raid shelters9. Other underground exchanges were built at Birmingham and Manchester known respectively as Anchor and Guardian. These were major works. Guardian for example is 112 feet underground and its main tunnel 1000 feet long and 25 feet wide. It cost £4 million in 1954, the equivalent of £50 million today.

The early plans envisaged the seat of government staying in London at least until the Whitehall area became uninhabitable but as early as 1949 the Working Party on War Rooms advised that it would be desirable to provide an alternative CGWR outside the London target area. Now Padmore, as well as saying that the seat of government should remain in London, specifically recommended that a reserve facility for the seat of government should be established outside London to be known as SUBTERFUGE. In response, the Home Defence Committee of the Cabinet said priority should be given to SUBTERFUGE over the proposed protective works in London because even if a nucleus of government survived in London the conditions would make it very difficult to exercise effective direction from it. Moving the seat of government from London was seen as “impractical for reasons of morale” but “after the blitz a shadow government in SUBTERFUGE takes over and if something survives in London and it can continue to exercise some nominal direction via SUBTERFUGE, so much the better.” Padmore also said local government could not be relied on after an attack and so the regional civil defence chain of command should be strengthened.

The Strath Report on Fall Out

Padmore took into account the effects of the hydrogen bomb which were beginning to be understood following the first test of it by the Americans in 1952. These effects, and particularly the impact of radioactive fall-out were spelled out in the 1955 Defence White Paper which said of the hydrogen-bomb, or “the megaton weapon”10 as it was often called, “If such weapons were used in war they would cause destruction, both human and material on an unprecedented scale. If exploded in the air, a hydrogen bomb would devastate a wide area by blast and thermal radiation. If exploded on the ground the damage by blast and thermal radiation would be somewhat less but there would be additional extremely serious indirect effects. A great mass of atomised particles would be sucked into the air. Much of it would descend round the point of explosion but the rest would be carried away and descend as radioactive “fall-out”. The effect on those immediately exposed to it without shelter would certainly be fatal within areas of greatest concentration of the “fall-out”. It would become progressively less serious towards the outer parts of the affected region. Large tracts would be devastated and many more rendered uninhabitable. Essential services and communications would suffer widespread disruption. In the target areas, central and local government would be put out of action partially or wholly. Industrial production, even where the plant and buildings remained would be gravely affected by the disruption of power and water supplies and the interruption of the normal complex inter-flow of materials and components. There would be serious problems of control, feeding and shelter. Public morale would be most severely tested. It would be a struggle for survival of the grimmest kind”.

The White Paper went onto say that all home defence plans would have to be completely overhauled as it was no longer possible to think in terms of the experience of the last war or even of the threat posed by atomic weapons. A new approach was called for but the White Paper said that until the implications had been fully assessed it would be unwise to do anything. But this was a deliberate attempt to keep the real effects of the H bomb from the public and the implications were in fact being assessed, and in great secrecy, by the Strath Committee.

This committee of 3 senior civil servants, 2 military officials and a scientist and chaired by William Strath, a Cabinet Office official working for the Central War Plans Directorate was set up in December 1954 to consider the effects of the hydrogen bomb and in particular the new phenomena of radioactive fall out. Its report delivered to the Cabinet some four months later was a pivotal event in British Cold War planning but one which remained secret for nearly 50 years.

The Committee considered the effects of 10 H-bombs each of 10 megatons dropped, at night, on British cities and which would result in “…a threat of the utmost gravity to our survival as a nation.” As well as blast, one bomb could produce up to 100000 fires. Fall out would create “…an inner zone of approximately 270 square miles (larger than Middlesex) in which radiation will be so powerful that all life will be extinguished…”. There would be 12 million dead and 4 million other serious casualties - one-third of the population. A further 13 million people would be pinned to their homes for at least a week by fall-out. This compares with the two and a half million casualties expected from the 132 A-bomb attack.

Apart from the loss of life “The houses of a very large proportion of the working population would be destroyed or rendered uninhabitable by ordinary standards as a result of widespread damage to roofs and walls by blast. The effectiveness of the surviving working force would be seriously reduced by illness…longer term effects would be primarily to reduce the economic power of the country…”. There would be destruction over half the country. Forty per cent of industrial capacity would be crippled with grave dislocation of essential utility services over a wide area. This, in turn, would disrupt the distributive systems of the country and interfere with ordinary social and economic processes including the mechanism of money transmission. Apart from the direct loss of food stuffs widespread contamination would affect most forms of agricultural production and water supply. There could be no reliance on normal imports for a considerable time and the survivors would have to subsist under siege conditions on whatever stocks remained. The continued effect of these and other consequences of nuclear attack would be to set up a “chain reaction” in the social and economic structure of the country. Even those not directly affected would suffer malnutrition and be unable to give their best in the work of restoration. A disproportionate loss of the working population and of key personnel might leave excessive numbers of “useless mouths11” among the survivors.

Some information about the immediate effects of the new bombs was given to the public in a civil defence booklet called simply “Nuclear Weapons” published in 1956. It compared the “nominal” atomic bomb with a yield of 20 kilotons with a new “nominal” hydrogen bomb with a yield of 10 megatons. Its readers were told that a hydrogen bomb exploding at the optimum height of 8000 feet would produce damage over an area 64 times as great as the atomic bomb. A figure that explains the authorities' private concerns that civil defence measures could simply not cope. The following table from the booklet shows the comparative blast damage ranges of 3 possible bombs -

| Effect on houses | Range for air-burst nominal bomb 1000ft high (miles) | Range for air-burst 10 megaton bomb 8000ft high (1 1/2 miles) (miles) | Range for ground burst 10 megaton bomb (miles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total destruction | ½ | 4 | 3 ½ |

| Irreparable damage | ¾ | 6 | 5 |

| Moderate to severe damage | 2 | 16 | 13 |

| Light damage | 3 | 24 | 20 |

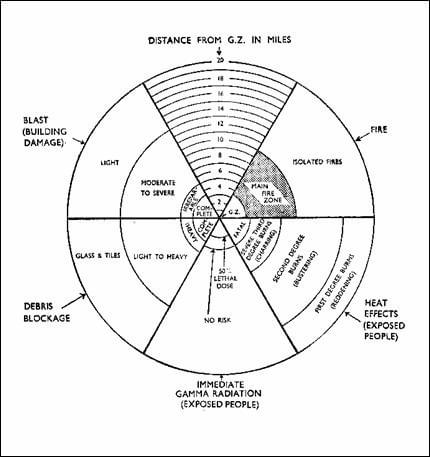

The booklet showed why the Strath Committee were so concerned about fall-out. It said that blast damage from both atomic and hydrogen bombs would be greater with airbursts, which would give only small amounts of fallout. However, the destructive range of a single hydrogen bomb was so great that if exploded at the optimum height of 8000 feet it would exceed the size of all British cities (with the notable exception of London). Consequently, a lot of the blast effect would be wasted. Military strategists therefore expected that the Soviet bombs would be set to explode at ground level where the blast would still destroy the entire city but also create a massive amount of deadly and disruptive fall-out. The diagram below taken from the booklet shows the effects expected from a 10 megaton ground burst at various distances from “G.Z.” or ground zero, the point of impact. Figures such as these have been disputed over the years but they show what the authorities were preparing for -

The following year the 1957 White Paper “Defence - Outline of Future Policy” was even blunter when it said “It must be frankly recognised that there is at present no means of providing adequate protection for the people of this country against the consequences of an attack with nuclear weapons.”

At this time the Joint Intelligence Committee, which advised the government on Soviet military preparations were suggesting that the Soviets were unlikely to launch a nuclear attack in the face of massive NATO retaliation and in any case the Soviets would not have sufficient nuclear bombs or aircraft to carry them to attack until at least 1958. This no doubt accounts in part for the slow build up of the civil defence response to the H bomb although it was assumed that the aim of any Soviet attack would be to -

- Knock out as soon as possible any airfields from which a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union could be launched.

- Destroy the organisation of government.

- To render the United Kingdom useless as a base for any form of military operation.

In practice, the Soviet Union did not have a meaningful strategic nuclear force until the early 1960s and then it would have had to take into account targets throughout North America, Europe and possibly the Middle and Far East. Soviet doctrine recognised the problems that Strath predicted but as material which has become available since the end of the Cold War shows it envisaged a different scenario to NATO and in particular US theorists. Like NATO, the Soviet planners assumed that the other side would attack first and with a devastating nuclear strike. But while NATO strategists assumed the strike would render further military operations impossible or irrelevant their Soviet counterparts expected that the Soviet lead Warsaw Pact forces would absorb it and then go onto the offensive. The strategic nuclear attack would be devastating but a nuclear war would still be winnable in the sense that the object would be to destroy the West’s ability to wage war on the Soviet Union both immediately and in the long-term. The initial role of Soviet nuclear forces would be to destroy NATO’s nuclear weapons, but then nuclear weapons would be used freely to support land operations in Western Europe. More significantly, once NATO’s nuclear forces had been destroyed, which would in itself cause massive civilian casualties, attention would be turned to directly destroying its population centres and economic infrastructure. The result was that the Soviet nuclear attack would be directed at civilian as well as military targets and would continue for as long as the war lasted.

The Strath Committee’s report recommended long-term policies such as siting factories and government buildings in safer areas, devolving work to regions, installing protected basements in new buildings and strengthening the regional organisation. More immediately, from a military viewpoint the report was traumatic. An attack on the scale envisaged would smash the UK home base and render it unusable for global military operations. The armed forces would need to be restructured for a much shorter war with little need for reserves of men or equipment. The focus of military activity would shift from fighting World War 3 to assisting the country during the survival period after it12. One consequence, for example, was the abandoning of Operation Knockout, the plan to repel an invasion and the subsequent closure of all the coastal artillery batteries left from the last war at places like Dover and Newhaven.

Despite the scale of the devastation Strath thought the country could survive and recommended large scale plans for public shelter and evacuation. The idea of requiring all new buildings to incorporate fall-out shelters was however quickly dismissed on grounds of cost and the problems that would result from older properties not having this protection. Evacuation was however considered and resulted in a plan to evacuate 11½ million people in the “priority classes”, mainly children and their mothers from the cities. The workers were expected to stay behind to ensure that the economy continued although some suggestions were made that this would be unrealistic and there were some ideas that plans could be made for the city workers to leave the towns at night and return in the morning - until presumably they were attacked and destroyed.

The Strath Report said it was impossible to forecast how people would react particularly if several bombs hit one city but “…there might be complete chaos for a time and civil control would collapse. In such circumstances the local military commander would have to be prepared to take over from the civil authority responsible for the maintenance of law and order and for the administration of Government. He would, if called upon, exercise his existing common law powers to take whatever steps, however drastic, he considered necessary to restore order. He would have to direct the operations of the various civil agencies including the police, civil defence services and the fire service. In areas less badly hit the civil authorities might still be able to function but only with the support of the armed services”. This suggests that martial law would be needed but later the report seemed to play down the idea when it said “Military authorities support the civil authorities in the maintenance of order and control and where necessary take over from them”. But, the idea of martial law was not apparently pursued and it was not even mentioned in the Chiefs of Staff’s discussions of the report. Instead, for the civil defence organisation, the first response to the report was to order an immediate strengthening of the administration. A Director General of Civil Defence had been appointed the previous year to co-ordinate plans at all levels but now the Home Office’s regional civil defence offices were enlarged and Regional Directors of Civil Defence (invariably ex-senior military men) appointed. These regional offices would oversee the civil defence preparations of the local authorities and look after regional level activities such as the War Rooms and exercises. At the operational level previous plans had assumed the Regional Commissioner would take on the powers and functions of the central government in the region if communications were lost with central government in London. This was now seen as virtually inevitable and to reflect this greater governmental role the Regional Commissioner would now be a government minister or a person of ministerial status rather than a member of what was referred to as “the great and the good”.

Joint Civil/Military headquarters

The existing Regional War Rooms would be too small both physically and in terms of staff numbers to direct the civil defence response to an H-bomb attack and to form the central government for the region. This lead to the idea of setting up a much larger joint “civil-military headquarters” in each region. In 1956 a nominal list of 441 staff was compiled (against the originally suggested 350). This list suggests that the intention was to establish a Regional War Room structure as before but with a much greater representation from the government departments and the armed forces to handle the post-survival period. The headquarters would still lead the regional efforts at “life saving” and it had a large military presence, which included the headquarters of the Army District, reflecting their increased role in the survival period and the large number of reserve formations now allocated to civil defence. But, the new headquarters would now have a more important and longer term role in acting as the government for the region until a proper central government organisation could be re-established months, possibly years, after the attack.

Some instructions for the new headquarters were written for Exercise Four Horsemen in 1958. These said that the “Regional headquarters would be, in effect a smaller nuclei of government at which, under the direction of a Regional Commissioner (in Scotland the Secretary of State) those departments having a home defence function would be stationed. The Regional Commissioner would execute government policy for so long as he was in contact with the central headquarters and act as the Government for his region if and for as long as he was isolated”. The headquarters would be manned at the start of the precautionary period when the Regional Commissioner would have specific powers delegated to him and then gradually assume responsibilities from the peacetime government machine. The Regional Commissioner would be supported by a Principal Officer, the peacetime Regional Director of Civil defence, Regional Police Commander, Regional Fire Officer, Regional Scientific Adviser, Principal Medical Officer and representatives from government departments and the district army command. The main government departments would be well represented according to their post-war roles and the largest contingents would come from the Home Office, Maff and the Ministry of Transport. The Regional Commissioner would be regarded as the effective central government authority for all home defence matters from the time he took up office but the devolution to him of powers would take place in stages. He and his staff would only act as agents for their parent Ministers until the central government nucleus took control when he would assume all powers except those specifically reserved for the centre but he would still act on any policy directives received from central government.

The 2 distinct but overlapping roles were summed up in Civil Defence Corps training notes from the time which said “In each civil defence region there will be in war a Regional Commissioner appointed by central government who will at the direction of central government undertake…

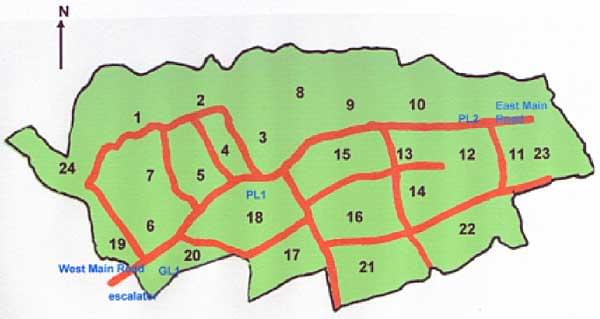

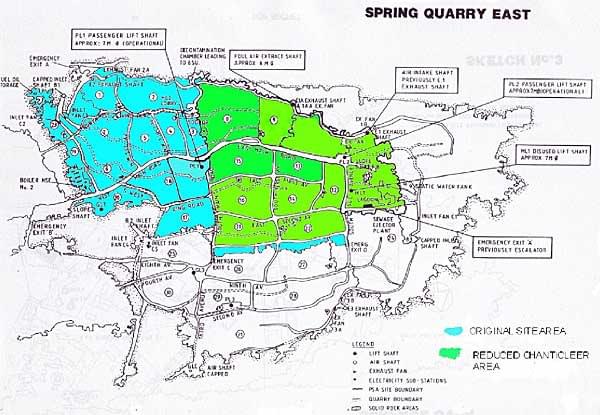

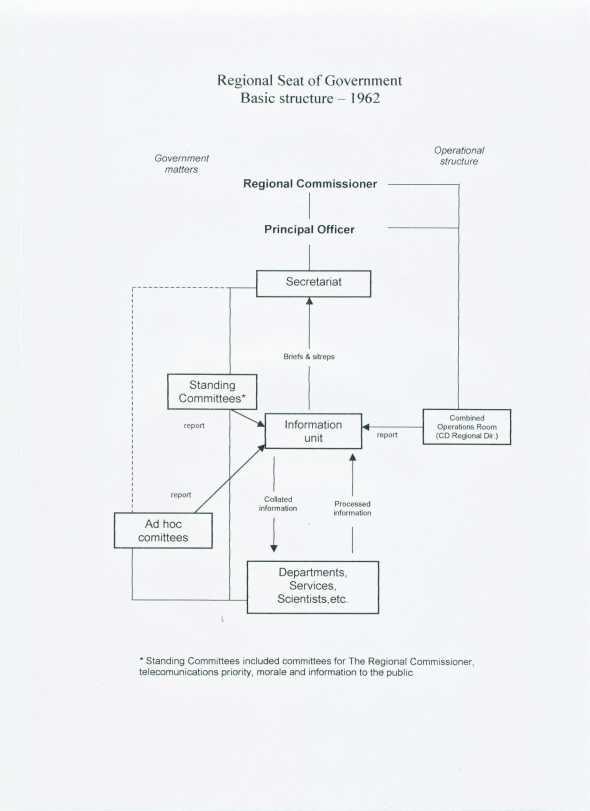

- Control of civil defence operations: the Regional Commissioner will have overall-ordination of civil defence operational arrangements in the Region.