Stockport, as part of the Manchester conurbation, expected to undergo heavy bombardment during the Second World War, and thus, when the Government tasked local authorities with the preparation of civil defence plans, Stockport’s councillors decided to extend old cellars and mine workings rediscovered a few years earlier during road improvement works, which they had been considering extending to create an underground car park. These cellars and tunnels had been excavated into in the relatively soft sandstone bluffs beside the river Mersey and seemed ideal for enlargement into large public air raid shelters.

Government pre-war policy though favoured dispersal, people sheltering at home or in small shelters if they were out and about or at work, and was strongly against large public shelters except in exceptional cases. Many authorities applied for grant funding for large or deep shelter projects and were refused grant aid, but Stockport opted to ignore this and go ahead anyway, trusting that they would ultimately receive financial support (which they eventually deservedly did).

Experiments with cutting different tunnel sizes led to the ideal size (approx. 2.1m wide x 2.1m high) being determined and several shelters were built in late 1938 and 1939. The largest of these, Chestergate, became the most famous, accommodating originally 3850 people before being enlarged to take 6500. This would come to be known as “the Chestergate Hotel” due to its comparatively dry conditions, good natural ventilation and atypically generous, albeit Spartan, facilities, including chemical toilets, electric lighting, a canteen and later bunk beds. The social life and communal support that existed in larger shelters also provided a greater feeling of security, something the Government had feared. One of their great pre-war concerns was that in larger and more heavily protected shelters a “shelter mentality” would lead to people not wanting to go back to work after a raid was over, with a consequent drain on the war effort. This does not appear to have been a problem at Chestergate although its popularity led to a great demand for places, and while a shelter ticket system was introduced to dampen down demand, shelter marshals were proud of their record of always finding room for whoever turned up and never turning anyone away

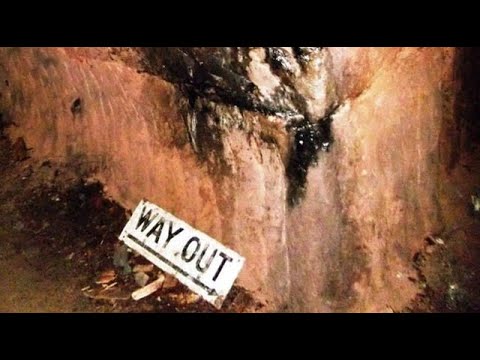

After the war the Chestergate tunnels were boarded up and forgotten, only being re-opened in the mid-1990s, when workmen found a network of interconnected vaulted tunnels about a mile long which were in surprisingly sound condition. The lighting and most timber benches had perished, but the steel and zinc bunk beds and 16-seater flushing toilets (which comprised a large brown salt glazed drainpipe with seats fixed on top of it) had survived. An ambitious plan developed to create a visitor attraction, becoming the first purpose-made public air raid shelters in Britain open to the post-war public. The shelter has proved to be popular with the public, attracting 50,000 visitors a year, and is Stockport’s top tourist attraction.

The public part of the shelter, however only uses a relatively small part of the tunnel system, and a plan subsequently emerged to have occasional guided visits into the unlit sections, with hard hats and head torches provided. This allows the more interested visitor to experience the whole of the rest of the system, seeing countless rows of bunk beds, different toilet layouts and degrees of preservation, and a concrete-lined section that had been rebuilt following subsidence during the war.

Visit by kind permission of Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council

More information can be found at Stockport Air Raid Shelters.