Following the outbreak of WW2 and the evaluation of the Chain Home (CH) and Chain Home Low (CHL) radars under operational conditions, a requirement was identified for a control radar to aid the fighter interception of enemy aircraft.

The coastal CH and CHL radars all looked out from the UK, leaving a void inland, this void relied on the Observer Corps (later Royal Observer Corps) for overland reporting, which was not effective in bad weather or at night.

The Ground Control Intercept (GCI) was designed to fill this gap, providing inland coverage to Filter Rooms, Sector Operations Centres (SOC) and Gun Operations Rooms (GOR) in addition to the control of defence fighters combating enemy aircraft by day and night. Sopley was operational 24 hours a day, every day, with a three watch system of staffing.

The GCI system had an extremely convoluted and complex history. The programme was subject to rapid change, some projects being superceded whilst still in the workshop, whilst others were conducted in the field and then retrospectively fitted to other radars. For example, in the spring of 1941 an experimental modification to the height finding at Sopley resulted in the other five original sets being ‘Sopleyfied’. Changes in enemy tactics also meant that the siting of GCI’s was constantly being subjected to review and revision.

The first GCI’s were mobile, at the insistence of the Air Ministry who required maximum flexibility from the equipment and were the first phase of a three part programme, i.e.: Mobile, Intermediate and then Final. The mobile radar convoy was called an AMES (Air Ministry Experimental Station) type 8 and ran to five variants AMES 8a, 8b, 8c, 8e and 8f (8d appears to have been cancelled). The type 8 consisted of 2 trailers each housing a hand turned aerial array for the transmitter and receiver respectively.

The transmitter was housed in a three ton Crossley Tender with the receiver in a second Crossley. The Operations Room was fitted on a four wheeled trailer.

Both Transmitter and Receiver were supplied with power from 2 mobile generators with 2 more in reserve. 2 vehicles containing HF (later vhf) radio transmitter and receiver completed the technical component.

The other type 8 radars were:

- 8a - Intermediate - mobile GCI with hand turned aerials and hutted operations and transmitter rooms

- 8b - Transportable GCI with additional 35' aerial system mounted on a gantry

- 8c - Intermediate Transportable GCI - as 8b, but with operations and transmitter rooms in huts

- 8e - Mobile GCI Mk IV

- 8f - Intermediate Mobile GCI Mk IV - as 8e, but with operations and transmitter room in huts

The 8e was a Mk IV GCI mobile with only a GCI capability, none of these 8e convoys were used in this manner. They were modified with conversion kits to provide facilities for GCI, COL (Chain Overseas Low) or CH (B) Chain Home, Beam) working and when converted became the AMES type 15 Mk 1 mobile GCI Convoy.

The mobiles were the first of three stages, the Intermediates were the second stage, pending the construction of the permanent, brick built, multifunctional ‘Final’ GCI with the much delayed Type 7 radar array built over an underground chamber containing the transmitter, and capable of conducting several interceptions simultaneously.

Operational trials started on the first Ground Control Interception radar station at Durrington (near Worthing) on 29th November 1940 and by 3rd December, 36 practice interceptions had been completed. With the success of Durrington, five more GCI stations were proposed with the first mobile installation established at Sopley in December 1940.

On Christmas Day, 1940 a convoy of vehicles arrived at Sopley and set up a mobile GCI installation in a field to the north of the village on land requisitioned from the estate of Lord Manners. This was called an AMES Type 8 which was designed so that the mobile equipment could be driven to the selected site and made operational within twelve hours. Personnel were billeted in the nearby villages of Sopley, Winkton, and Ripley.

The mobile Type 8 radar was designed at the Telecommunications Research Establishment at Worth Matravers in Dorset and built at the War Office/Ministry of Supply Air Defence Research and Development Establishment (ADRDE) in nearby Christchurch. It was adapted from Army Gun Laying trackers and had two manually rotated aerials rotated by airmen pedalling in the cabin mounted on the aerial trailer behind the aerial array.

The aerial’s alignment onto a target was originally a manual process with airmen pedalling to operate a mechanical linkage to turn the aerial. The fighter controllers used a bell code and mechanical indicators. The aerial’s sweep could also be reversed or concentrated in a defined sector of the sky giving a more frequent update of the track information than a 360 degree scan during the later stages of an intercept.

The transmitter aerial was fed by a transmitter in an adjacent lorry while the receiver aerial was fed into the operations trailer via a receiver vehicle where a range of displays indicated bearing, range and height and incorporated a Plan Position Indicator [PPI] display with the radar display equipment to drive the PPI’s in the Control Van

The ops room had a crew of three, a height finder operator, a fighter controller and a plotter. From the beginning Sopley seems to have been equipped with Identification Friend or Foe (IFF).

IFF allowed a radio operator to identify friendly aircraft. Aircraft were fitted with aerials incorporating motor-driven tuners that caused the reflected signal received by ground radar stations to vary in amplitude.

Later models employed an electronic unit that detected the presence of friendly radar and then transmitted a coded signal causing the ground radar display to indicate a friendly aircraft on the PPI display.

By early 1941, Sopley had become the most effective GCI station with over one hundred successful night interceptions which were achieved by the fighter controllers at Sopley working in conjunction with Bristol Beaufighter night fighter squadrons who destroyed 27 enemy aircraft, more than twice the success rate of any other GCI.

The GCI station operated throughout the second world war using the callsign ‘Starlight’ and gave radar assistance and control to many squadrons operating initially from RAF Middle Wallop and later from RAF Hurn. Sopley was also responsible for the control of No 456 Squadron RAuxAF from RAF Tangmere, towards the latter part of the war.The early mobile installation was replaced in 1941 by an ‘intermediate mobile’ with a pair of type 8F radars followed later by an ‘intermediate transportable’ GCI; utilising a Type 8C radar.

This was an unusual arrangement, the normal course of events was for one or the other but not both.

Possibly Sopley, being the first production radar (Durrington was a prototype) was used as a test bed or trials site for new equipment or practices. The equipment was mobile to the extent that it could be easily dismantled and transported to another site. The erection was a fairly lengthy process taking several days to complete. The arrays were mounted above and below a wooden gantry, with operations carried out from wooden hutted control rooms.

By 1943 the station had evolved into a GCI ‘final’ with a brick operations blocks, known as a ‘Happidrome’ (named after a BBC comedy radio programme featuring a farcical music hall where nothing seemed to go as planned and nobody quite knew what was happening - much like a GCI!!) in an adjacent field on the opposite side of the road to the intermediate site.

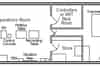

This consisted of a large brick built control centre with integral machine and plant rooms, a telephone exchange, GPO equipment room and an operations room with intercept cabins in raised galleries around the reporting room floor.

The reporting room had two horizontal plotting tables with a vertical ‘Tote’ board detailing the status of flights and raids which could be viewed from the elevated controller’s cabin. One plotting table at Sopley showed the regional situation, the other the local picture.

From the elevated cabin, a Supervisor would oversee the entire situation whilst an Allocator would allocate fighters and intercepts to individual fighter controllers, who would then control the radar interceptions. The controllers and their assistants were situated in cabins behind the controller. There would be direct phone lines to the wider air defence organisation, manned by an assistant.

On the plotting table metal arrows show the position and direction of contacts. WAAF’s used metal poles with magnetic tips to manipulate the arrows which were colour coded in coordination with an RAF sector clock with 5 min colour sectors to show the most recent plot information.

If the station was busy, a WAAF supervisor maintained the wall mounted tote board and added additional data to the arrows such as a contact number and a classification of the contact as Hostile or Friendly. The tote board would have listed the local RAF night fighter stations, including Hurn and Middle Wallop, their night fighter squadrons with whom Sopley worked the aircraft available and their status

A standby generator was housed in an adjacent building (standby set house). The final installation had a single rotating aerial array with the transmitter and receiver housed in an underground well beneath.

The station was built for an AMES Type 7 search radar initially operating on a frequency of 209 MHz, and later on 193 and 200 MHz. This was a parallel development of the Chain Home Low (CHL) equipment by the addition of a height-finding capability and a Plan Position Indicator (PPI) display. In a PPI display the cathode ray tube is scanned radially from the centre of the tube face. The bearing of the scan is synchronised to the rotating aerial and the intensity of the beam is modulated by the signals received from the aerial.

The effective range of the GCI station was 90 miles with a range of 30 miles at 1000 feet. In order to provide communication between the controllers in the Happidrome and the intercepting aircraft, two VHF/UHF multi-channel radio transmitter and receiver blocks were built at remote sites to stop interference and swamping of the radio signals by the radar arrays. Sopley GCI also provided information for anti-aircraft (HAA) gun sites. In 1943 Winkton Airfield was built a short distance to the south east of the radar site. It acted as an advanced landing ground for the 404th Fighter Group of the American 9th Airforce coming into use on 4th April 1944.

Prior to the invasion of Europe in June 1944 Allied use of ‘window’ had proved a great hindrance to CH, CHL & GCI wavelengths. Therefore high frequency equipment was installed at certain GCI stations where the narrow beam width would reduce the echoes from ‘window’ to a minimum. This equipment was entitled AMES Type 21 Mk1 and consisted of two equipments: AMES Type 14 Mk 3 and AMES Type 13 Mk 2; both centimetric sets. The former consisted of a PPI unit rotating at 6 rpm and the latter was the associated height finding unit capable of giving a height reading in any direction. 15 GCI stations were thus equipped in early 1944, all being installed and operational by June, RAF Sopley was one of these stations. (Ref: radar in raid reporting App 51)

(Window was a jamming technique consisting of half wavelength strips of aluminium which were dropped in bundles from aircraft; it was shiny on one side and black on the other. When bundles were dropped every strip reacted as an aircraft to German radar)

Following the end of the war the air defence system was reviewed in the light of experience and a now much reduced budget. One outcome of this was to nominate one GCI station in each sector to be an SOC/GCI (Sector Operations Centre) which was in effect the reserve SOC should the main SOC become non-operational. This upgrading involved the construction of an extension to the operations room to accommodate four new cabins with two windows overlooking the reporting hall, whist the intercept cabins behind the chief controller were rearranged and enlarged, the RT monitors being relocated in the admin section. These SOC’s remained in use until superceded by the R3’s, R6’s and R8’s of the rotor system. Sopley became the SOC/GCI for the Middle Wallop Sector.

Sopley continued to operate as a GCI station, becoming the Sector Operations Centre for Southern England in 1950. By 1950, the threat of the atomic bomb had caused a serious rethink in the organisation of air defence and a plan, codenamed ROTOR, was instituted to replace many of the existing stations with new protected underground operations rooms. For GCI Stations these were designated R3 (west coast GCI stations which did not require the same level of protection were located in R6 surface blocks).

The R3 was never intended to survive a direct hit from a nuclear weapon but was designed to withstand a near miss from Russian pattern bombing with 2,200lb armour piercing high explosive bombs (BRAB) dropped from 35,000 feet. It was decided to rebuild the GCI station at Sopley on the opposite side of the road to the happidrome in the field originally occupied by the mobile installation in 1940.

The new station became operational in the summer of 1954 using the callsign ‘AVO’; it was fitted with the following radars: one Type 7 Mk. II, one Type 11 (Mobile) Mk. VII, two Type 13 Mk. VI, two Type 13 Mk. VII, one Type 14 Mk. 8 and one Type 14 Mk. 9. A new domestic camp for 450 personnel was built near Bransgore village but until this was complete accommodation was provided until 1952 at RAF Ibsley which had closed as an active base in 1946.

During 1956 Decca Type 80 Mk. III search radar was installed, replacing the earlier Type 7. The Type 80 was developed in the early 1950’s from an experimental design based on the Type 14 Mk VI under the project code name Green Garlic. At this time the two Type 14 radars were dismantled and removed

Almost overnight this new radar made parts of the ROTOR air defence system redundant. The Type 80 improved the range of the station considerably with a range of up to 320 miles compared to the 90 mile range of the Type 7; this instantly made some of the earlier equipment obsolete.

Inside the R3, dramatic changes were also taking place. The large two storey operations room was superseded by a much smaller control room constructed on the top floor at the opposite end of the building. This included a ‘well’ in the floor for a photographic display unit (PDU) which allowed radar pictures to be projected up into a plotting table from the room below housing a Kelvin Hughes Photographic Projector.

This consisted of equipment that could record the radar image on 35 mm film, develop, fix and dry the image and then project it up on to the plotting table in the control room on the floor above. The displayed image was one minute behind real time. The PPI image from a high intensity cathode ray tube was projected on to the film through a focusing lens. Each revolution of the radar antenna took 15 seconds and it took this time to expose the film to a full revolution.

At the end of the sweep, the frame would be moved on to be developed, whilst the next frame was exposed. When the frame moved on at the end of the next sweep the image was fixed, it then moved on again to be dried. Finally the frame moved on once more where it was projected, via a mirror, to the underside of the frosted glass plotting table on the floor above.

Meanwhile the next frame to be exposed has been following on through the process, so at the end of the next revolution this frame was projected, 15 seconds after its predecessor.

Finally the frame moved on once more where it was projected, via a mirror, to the underside of the frosted glass plotting table on the floor above. Meanwhile the next frame to be exposed has been following on through the process, so at the end of the next revolution this frame was projected, 15 seconds after its predecessor. As frame after frame was displayed on the map the plotters in the pit could place markers on the map to indicate friendly or hostile aircraft.

With the installation of the Type 80, the Station continued to operate in the Air Defence Role as a Fighter Control Unit manned by members of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force and while many stations closed Sopley was required for the 1958 Plan.

In January 1958, with the expansion of the Air Traffic Control system in the UK, a Squadron Leader, the officer commanding the Air Traffic Control Research Unit (ATCRU) and several controllers arrived at Sopley to set up an ATCRU Area Radar Service covering the Home Counties, the Midlands, South Wales and the West Country and Southern Radar was formally established on 1 April 1959.

In 1958, the School of Fighter Control moved from Hope Cove to Sopley together with a Special Tasks Cabin, to look after both the military and civil research and development requirements and also to afford control facilities for fighter interception practice for RAF Chivenor; it was collocated with the ATC unit.

No. 15 Signals Unit was formed with effect from 28th October 1959 from the Air Traffic Control radar section at RAF Sopley. The operational tasks in order of priority were as follows:

- Assistance to Air Traffic Control Centres in the control of emergency incidents

- Military aircraft crossing civilian airways

- Extended approach control to selected airfields

- Surveillance of military aircraft in transit through Flight Information Regions

15 Signals Unit comprised 1 Squadron Leader, 3 Flight Lieutenants, 3 Flying Officers/Flight Lieutenants, 1 Warrant Officer, 3 Flight Sergeants, 3 Corporal clerks, 11 Aircraftsmen clerks. The unit was parented by RAF Sopley

In July 1959, the Air Defence reporting element of the Unit moved to RAF Wartling releasing extra radar facilities for the ATCRU use and on 1 November 1959 the ATCRU took over from Air Defence the responsibility for the Special Tasks cell.

In April 1960, the School of Fighter Control was disbanded and the station was handed over to the ATC; the Unit then had a direct responsibility to HQ United Kingdom Air Traffic Control Services (UKATS) which had been previously established at Kestrel Grove adjacent to Bentley Priory. By 1 July 1960 the fighter control training facilities had been modified and the training of military Area Radar Controllers commenced and in September 1960 and the Joint Air Traffic Control Area Radar School (JATCARS) was formed.

During the early 1960’s three of the Type 13 height finder radars were replaced with the AN/FPS 6, the fourth Type 13 remained in use and operational until the closure of the station. In January 1961, two radar control positions in the Operations Room were allocated to the Ministry of Aviation for the control of civilian air traffic passing through the Southern Radar area on the newly formed Upper Air Routes.

The unit now functioned as a joint civilian and military air traffic control radar station.

Development in radar design between 1958 and 1966 led to the installation of new height-finding equipment and the Type 264 Radar. Southern Radar was now a Military Air Traffic Operations (MATO) Unit; UKATS having been renamed. The 264 was a civil radar for use by the civil ATC part of Sopley. When Sopley closed it was relocated to Aberdeen airport where is provided many more years of service.

The civil area control course had been at the civil School of Air Traffic Control at Hurn since the 1950’s. With the growth in the use of radar by ATC, two new problems arose - firstly the civil school had too few simulator positions to cope with the number of students to be trained and secondly there was a need to improve civil/military understanding. As it was so close to Hurn, it was decided to use spare capacity on the military courses at Sopley to help solve both problems.

In 1969 the civil side of the Area Radar School moved back to Hurn and JATCARS became the Military Air Traffic Control Area Radar School (MATCARS), continuing to train Military Area Radar controllers until its closure and subsequent move to RAF Shawbury, in August 1972. From 1959 to 1972 Southern Radar had provided Operational Control to Air Traffic over the whole of the South of England.

With the implementation in 1972 of the Linesman/Mediator plan for centralised Air Traffic Control Services, Southern Radar’s Area of Responsibility was gradually reduced, leading to the eventual handover of Southern Radar services to London Air Traffic Control Centre at West Drayton in 1974.

The Sopley Air Traffic Control Centre was now surplus to requirements and RAF Sopley closed on 27th September 1974.

In about 1975/76 the bunker was occupied by a Royal Signals unit from Signals Research and Development Establishment at Christchurch. The bunker was reported to have been extensively rewired at the time and at some cost. The local rumour was that it was an elint (electronic intelligence) lodger unit formerly located within SRDE that wasn’t going to relocate to Malvern in 1980 with the rest of the establishment. There were no additional aerials other than base-to-vehicle local VHF type aerials.

In 1977 the bunker was designated as a sub Armed Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) for Region 6 although nothing done to prepare it for this role. Warren Row was also a sub AFHQ6 and by 1980 only one of the two sites (Warren Row) was required.

The 1980 Bournemouth Borough War Plan shows Sopley as an Army Headquarters. The bunker was taken over by a unit from 2 Signals Brigade from UK Land Forces at Wilton and it underwent a major refit. A new central operations area was constructed. A new floor was inserted into the old two level operations room with supporting pillars below, this was at the same level as the upper floor of the R3; the upper space was divided into two new rooms.

The ceiling height of the lower floor of the ops room was still quite high as it incorporated the height of the 8' high cableway (includes 1' thick floors) that existed between the floors of the R3 and the true floor of the R3 which is 4' below the normal corridor and room level.

The tote was removed but its supporting framework was utilised as foundations for broad gallery extending over the operations floor. The original stairs at the left end of the gallery were retained, while a new stairway was provided at the other end parallel with the rear wall.

The original control cabins overlooking the ops floor were also kept. The single cabin across the right end of the room was unaltered. The next cabin, the first along the room’s length was also unchanged, except for an internal partition wall, with a doorway, put across the width of the room. The central open fronted projection room had a window filling the space above the counter and a new door above the existing steps. The remaining cabin had a new door inserted in the previously glazed front, leading to a new set of steps directly in front of the original entrance steps.

The floor of the ops room was fitted with a series of booths and low partitions, providing separate work areas. A lot of the structural changes were in an unfinished state, with a primer paint finish.

The PDU well was floored over and the lower part of the PDU (Kelvin Hughes room) was converted into a computer room and the rest of the lower PDU area became a COMCEN with some new air conditioning being installed.The project was eventually to provide a protected HQ for UK land forces in the event of a strike against the UK. However this was only ever envisaged as a temporary solution and was only intended to be used during the construction of a totally new facility which was being built for the army at UKLF Wilton.

Once this was completed UKLF no longer needed Sopley and it was put into the disposal process eventually being sold.

As a consequence of the promt construction of a new HQ at Wilton, the project to refurbish Sopley was not completed and some rooms were not fully decorated and finished. However the site was regularly used for training and exercises mainly involving overnight accommodation and using mobile and field communications; it was not a popular posting. The COMCEN and computer systems were all fully installed and operational and if there had been an emergency at this time the facility could have been used operationally. This use ceased at the end of the cold war.

RAF Sopley was put up for sale in 1993, the original landowner Lord Manners had first refusal to buy back all the domestic site as it was requisitioned from his father. He chose to buy back just the large area of open ground at the back of the domestic site for forestry and agriculture. The camp itself was sold to a local partnership under the name Merryfield Park. The technical site including the R3 bunker was sold for £150,000 to a document storage company and it has been sold on several times since then. It is currently owned by an American company who don’t allow any visits. They have recently tidied up the bunker site and repainted the guardhouse in bright white paint again.

In order to provide communication between the controllers in the R3 bunker at RAF Sopley and the intercepting aircraft, two large VHF/UHF multi-channel radio transmitter and receiver blocks were at built at remote sites. The blocks were remotely sited to stop interference and swamping of the radio signals by the radar arrays.

Rotor transmitter and receiver blocks come in two sizes, designated ‘small’ and ‘large’; those at Sopley, which have both now been demolished were ‘large’. Each block would have had a 90' wooden aerial tower alongside.

Each site consisted of two buildings, the operations building and a standby set house. The transmitter building was located on Dur Hill Down (SU195013), 3.5 miles northeast of the technical site; the building comprised the transmitter hall, mechanical and electrical room, store, workshop, staff room and toilet.

The smaller receiver building was at next to the old WW2 bomb dump on Holmsley airfield, a further mile to the northeast (SU209002) and comprised a receiver room, mechanical and electrical room, store, workshop, staff room and toilet.

The station was connected to mains electricity but in the event of a failure of the mains supply and emergency generator was provided. This was housed in a building called a ‘standby set house’ (this is an RAF only term) which was located within the domestic camp; the building is still extant.

The dispersed Sopley Camp is on the north side of Derritt Lane has had many uses over the years. With the closure of RAF Sopley in 1974 the camp was vacated by service personnel and for many years the site was used as an adventure training camp by the ATC.

During the Queen’s Silver Jubilee year in 1977 the domestic camp was taken over for twelve months as a rest and recreation centre for the Household Cavalry.

All the horses and riders spent a couple of weeks at Sopley in rotation as a break from the increased amount of ceremonial duties in London. They were very popular locally and the experience was apparently good for the Cavalry too. As a result the Cavalry sought permission from Ministry of Defence to take over the site, but were turned down.

Between 1979 - 1982 the camp was used as a reception and resettlement centre for Vietnamese refugees fleeing from the oppressive regime in their country. More recently the camp has been used as a training centre for the Wessex Fire and Rescue Service.

Most of the buildings are largely intact and in good condition considering their age. a few have now been put to industrial use.

In the early 2000’s part of the site was used for a variation of paintball known as Urban Airsoft involving close combat this use ceased in August 2004.

In November 2003 there was a proposal to return the site to forest and in March 2006 Merryfield Park who own the camp began market some of the huts as ‘freehold investment suites where owners can reside work and rest’ with prices between £60,000 and £120,000.

The site is licenced as a training and rest camp and a number of huts have been refurbished with all the amenities needed for this. They have newly fitted kitchenettes, shower-rooms and space for use as overnight accommodation for residential training courses or even for owners to stay overnight.

Two huts have already been sold as the first phase of the 27 unit development but planning regulations say that residential use is limited to occasional overnight stays for people involved in training or recreational courses.

RAF SOPLEY TODAY

Most of the surface buildings of RAF Sopley have been demolished with no evidence of their location remaining; these include the happidrome, radar plinths and the Type 80 modulator building. The R3 bunker is still in use as a secure storage facility and the guardhouse and associated buildings still stand on the west side of a minor road half a mile north of Sopley village within a large secure compound with a very low mound giving little evidence to the unsuspecting passer-by that there is a bunker beneath.

The guardhouse is not the standard Rotor bungalow design; it has an overhanging flat roof, similar to that at Portland and is painted white. The only other buildings on the site are the former generator house alongside which has now been stripped out and is used as a garage and a small blockhouse near the south west corner of the compound which houses the emergency exit. There is no indication on the property as to who owns it and what business is conducted.

In May 2000, two members of Subterranea Britannica were allowed into the bunker by the previous owner. We were given a full tour of the bunker but were only allowed to photograph those areas and rooms that did not show any evidence of document storage.

We descended the stairs to the lower floor where the main plant room still in excellent condition and fully functional with an impressive array of 1950’s plant. This is a very complex room divided into several distinct areas with partition walls. The plant and electrical switchgear is largely unaltered from Rotor days and is probably one of the best preserved AC plant rooms, in its original condition in any of the remaining R3 bunkers, (Holmpton is in a similar condition). The room is entered through double doors and down a short flight of steps. On the right is the control equipment for the air conditioning plant. This takes the form of large electrical control cabinets. On the left are two 3 cylinder compressors. These compress the refrigerant (originally the toxic anesthetic liquid, Methyl Chloride). Mounted on the wall behind there are two cylindrical horizontal tanks where the cooled water from the air cooled heat exchangers cools the refrigerant.

Between the two compressors are the oil separators Number 1 and 2; these separate the compressors lubricating oil from the refrigerant for compressors number 1 and 2 respectively. At the back of the room there is a panel showing the temperature and humidity in the system and various rooms. There were wet bulb hygrometers for this located in various places in the bunker. In the centre is a black dial this is used this to select what is monitored and the various parameters are displayed on the dials above.

Large diameter brown pipes, each contains the send and return refrigerant lines from the two compressors, these lead into the Baudelot heat exchanger which is located at a higher level and accessed by a ladder. This cools the water which is fed to the cooled water header tank in a small room at the top of the ladder; the air cooler batteries A, B, C and D are fed from here. Air cooling in the Rotor series bunkers was via water cooled cooler batteries - more modern designs used electric air heaters. The feed to and from some of these water cooled batteries (located in a separate room) are the large insulated green pipes

In a partitioned area diagonally opposite the entrance steps is the main air conditioning fan with two sets of filters on either side. To the rear of the Baudelot heat exchanger there are two narrow doorwa