HISTORY OF RAF PORTREATH

RAF Portreath was opened as an RAF Fighter Command Sector Station and Overseas Air Dispatch Unit (OADU) on 7th March 1941 as part of 10 Group whose headquarters was at RAF Box at Corsham. Prior to this, the Sector Station had been at St. Eval. An unusual feature of the station was four tarmac runways, although only the main runway was suitable for anything other than a single seat fighter. Twin blast pens and four blister hangars were spread out around the perimeter track and at a later date four T2 hangars were also built on the technical site. 263 Squadron was the first to arrive at Portreath, providing defence for the Western Approaches with the Westland Whirlwind Mk 1 fighter; they were soon replaced by Spitfires as Portreath took an active role as a fighter station.

On May 11th 1941 a Fighter Sector Operations Centre was opened at Tehidy Barton Farm, two miles south west of the airfield; on the opening the station took added responsibility for the satellite airfields at St. Mary’s (Scilly Isles), Perranporth and Predannack. In early May, Bristol Blenheim light bombers arrived at Portreath and their airfield was used as an advanced base for raids on France, although the main runway was only just long enough for a heavily loaded Blenheim.

Early in the war, RAF Kemble became host to a unit that prepared aircraft for service overseas, mainly the Middle and Far East. No. 1 Overseas Aircraft Preparation Unit (OAPU) was established at Kemble to carry out the task of modifying aircraft to operate in these regions. After modification aircraft were flown to Portreath from whence they were despatched to their destination; Portreath’s geographical position making it an ideal departure point for North Africa.

In October 1941, a detachment of the Honeybourne based Ferry Training Unit was established at Portreath to organise ‘ferry flights’ for crews that had been trained for overseas flying duties. The influx of crews during this period stretched the available hutted accommodation to its limit and a colony of tents was established on the hillside to provide additional crew quarters. During October 1942 the airfield was selected to take part in ‘Operation Cackle’ which involved the supply of aircraft, aircrew and supplies for the USAAF 12th Airforce to take part in ‘Operation Torch’ which was the Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa.

During the first half of 1943 Portreath was almost entirely committed to ferry operations. In July 1943 a new Sector Operations Centre was opened at Tregea Hill overlooking Portreath, one mile south west of the airfield, however it was little concerned with operations at Portreath which now mainly consisted of coastal strike and anti-fighter operations over the Bay of Biscay. Portreath remained busy during the build up to D-Day when 248 Squadron equipped with Mosquito VI’s mounted five separate missions.

After D-Day, sorties over the Bay of Biscay were few and far between and following the last sortie on September 7th 1944 the coastal squadrons were transferred to Banff in Scotland and the station went quickly into decline just leaving the Air Sea Rescue Squadrons and 1 Overseas Air Despatch Unit. The ASR squadrons left in February 1945. The last flying unit left Portreath in May 1945. The station was transferred to to 44 Group (Ferry Service) of Transport Command during that month and 200 aircraft were delivered overseas and a Transport Command Briefing School was established on the airfield but this was short lived. An overland route was now available to the Middle and Far East and with Portreath unable to handle transatlantic traffic, movements rapidly declined. The OADU was transferred to No. 2 OADU at RAF St. Mawgan in September 1945; the Briefing School left on 8th October and Air Traffic Control ceased on the following day.

In December 1945 the station was reduced to Care and Maintenance transferring to Technical Training Command in May 1946 for use by 7 (Polish) Resettlement Unit. When this unit moved out the airfield was abandoned.

RAF PORTRETH BECOMES CDE NANCEKUKE

The United Kingdom’s investigations into the military possibilities of organophosphorous compounds received an enormous post-war impetus from the stockpile of captured German nerve agent and research documents concerning Tabun and Sarin. Sarin was quickly identified as the most suitable agent for the UK services and by 1950 development was sufficiently advanced for limited production to begin. It was clear that the Chemical Defence Establishment at Porton Down was unsuitable for this work due to its proximity to large centres of population and industry. A new, remote location was therefore sought and the abandoned coastal airfield at Portreath in the sparsely populated area of the Cornish peninsula was considered ideal.

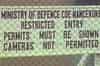

The site was taken over by the Ministry of Supply and renamed CDE Nancekuke. Added security was introduced with a new 9' high wire mesh perimeter fence and the closing of all approach roads. At that time there was virtually no public knowledge of the work and the non-scientific workers employed to build the plant were not told of its intended use. It was intended that the huge site, extending to several hundred acres, should initially be home to a small scale Sarin production plant under-taking process research work, but plans were already being prepared to build a vast, fully automated Sarin production and weapon-filling plant there.

CDE Nancekuke began operating as a small-scale chemical agent production and research facility in 1951. CDE Nancekuke operated 3 sites: North Site, Central Site and South Site. A pilot production facility was built on North Site to support the research, development and production of a nerve agent known as Sarin (GB) and Nancekuke became the prime centre in the UK for production and storage. Production at this plant commenced in 1954 and continued until 1956. During this period it produced sufficient Sarin (GB) to prove the process and to meet the requirements for assessment trials and the testing of defensive equipment under development at Porton Down. Subsequently, international tension relaxed to the point where it was not judged necessary to proceed with a production plant and production ceased in 1956 by which time a stockpile of some 20 tons had been accumulated.

CDE NANCEKUKE FROM 1956

From then on, work at Nancekuke concentrated on the small-scale production of chemicals and agents to support the UK’s defensive research programme which was being directed from Porton Down. Between 1956 and the late 1970s, CDE Nancekuke was used for the production of riot control agents such as CS gas which was manufactured on an industrial scale from about 1960. The CS plant produced the agent on a batch process at the rate of 30 kg per day with some 33-35 tons being manufactured in total. Nancekuke was increasingly involved with the development of medical countermeasures, training aids, and the development of charcoal cloth for use in protective Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical (NBC) suits used by the British Forces.

CHEMICAL CLOSURE AND DISPERSAL

In 1976, a defence review recommended the transfer of remaining work to CDE Porton Down, and the decision to begin decommissioning CDE Nancekuke was taken. A team of international inspectors oversaw the decommissioning process and the site is still open to inspection by members of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

All remaining stocks of chemical agents were destroyed or transferred to Porton Down between 1976 and 1978. Some chemicals were either neutralized on site or returned to the commercial chemical industry, but a considerable volume was buried on site along with debris from dismantled plant and buildings. At the time, this was considered to be an environmentally acceptable procedure. Material was dumped in five clearly defined and widely separated locations within the boundary of the Nancekuke site. One site was an old quarry some 40 or 50 feet in depth, this was filled with rubble and steelwork from the demolished factory along with similar material from surviving Second World War airfield buildings that had been reused for chemical purposes. Close to the cliff edge four specially excavated pits each 2 metres in depth were excavated and filled with waste chemicals from the factory. Nearby, the ground level of a shallow valley leading to the cliff edge was raised by about 20 feet by the deposition of building rubble, waste chemicals and quantities of asbestos from demolished buildings. More worryingly, two deep, long-abandoned tin mine shafts within the factory perimeter were used to dump surplus equipment from the Sutton Oak research establishment at the time that its function was transferred to Nancekuke. The problem with landfill is that what goes under the ground inevitably comes out in the water. Currently, in the United Kingdom, the problems of serious ground and water contamination from buried military waste are having to be addressed. The only safe solution is to recover these contaminants and treat them by chemical or physical means to ensure that their future environmental impact will be neutral. To comply with current legislation the site is now being cleaned up under the Nancekuke Remediation Project This process has just begun at the time of writing and is expected to be completed by the end of the decade. The CDE moved out in 1978 and the station reverted to the Ministry of Defence as a radar station.

COLD WAR RADAR

The Linesman radar system had become fully operational in 1974. In 1971 it was proposed that command of the United Kingdom Air Defence Ground Environment (UKADGE) was maintained centrally at two sites, West Drayton and Strike Command (HQ) at High Wycombe with control allocated to four control and reporting centres (CRC) at Buchan, Bishopscourt, Boulmer and Neatishead. The sites were able to exchange data by digital links with any of the sites able to take over from one of the others in an emergency. This new network was planned to give full coverage of the approaches to the UK and was fully integrated into the wider NATO air defence system.

Once implemented the system was somewhat different incorporating three elements; fixed Sector Operations Centres, Control and Reporting Centres, and mobile radars. The UK air defence region was divided between North and South controlled from SOC’s at Buchan (north of Aberdeen) and Neatishead (Norfolk) with Ash acting as a training unit and capable of taking over from either one of the SOC’s in the event of an emergency. Below the SOC’s in the hierarchy of control were the Control and Reporting Centres or Posts (CRC’s were underground and CRP’s were on the surface) with display consoles identical to those at the SOC’s. Their task was to create a local air picture of flying activity which was then relayed to the SOC’s. After fighter interceptors had been scrambled, control and reporting centres might assume the tactical control of the fighters. A CRC was established at Boulmer with CRP’s at Portreath, Faeroe Islands, Saxa Vord (Shetlands), Benbecula (Hebrides), Bishopscourt (Northern Ireland), Staxton Wold (Yorkshire) and Ty Croes (North Wales).

The first plans for a CRP in the West Country covering the East Atlantic approaches were drawn up in 1974. The proposed site was at Burrington adjoining the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) radar site. Burrington was quickly dropped due to perceived problems with interference and coverage in favour of a joint RAF/CAA site on the disused Winkleigh airfield in Devon. Here a Type 84 radar was proposed for the RAF and an SCR264 radar for the CAA. Before work on the site could be started the Type 84 was deleted from the national plan and the CAA station was never built.

With the closure of CDE Nancekuke in 1978 the old airfield at Portreath was selected as the best site with staff accommodated at RAF St. Mawgan. Because of the delays in selecting a suitable site it was vital that the new radar station was quickly established. No. 1 Air Control Centre arrived from Wattisham in July 1979 with the new station coming on line early in 1980 with a Type 93 mobile radar and refurbished WW2 buildings and portacabins. The station was formerly reopened as RAF Portreath on 1st October 1980. A new semi-sunken CRP bunker was finally built c.1988 and extended in c.1992.

DOWNGRADING

Following the end of the cold war and the reduced expectation of an air attack on the UK RAF Portreath was downgraded to a remote radar head parented by RAF St. Mawgan.

RAF Portreath is still operational as a Reporting Post with a remote radar head within the UK Surveillance and Control System (UK ASACS) which provides up to date information on air activity required to defend the UK and NATO. The UK ASACS is a highly sophisticated computer-based system which gathers and disseminates information on all aircraft flying in and around the UK Air Defence Region - this is known as the Recognized Air Picture (RAP). The information within the RAP is used by the Air Defence Commander when deciding whether to investigate or perhaps even destroy an aircraft flying in an area without permission. Information is fed into the RAP from the RAF’s ground-based radars and from the air defence systems of our neighbouring NATO partners. However, the UK ASACS can also receive information via digital data-links from other ground, air or sea-based units including No 1 Air Control Centre, which as a part of the UK’s Rapid Reaction Force holds a high state of readiness to deploy world-wide in support of crisis. The United Kingdom Air Operations Centre (UKCAOC) is situated within Headquarters Strike Command at RAF High Wycombe.

The UK ASACS has two operational Control and Reporting Centres (CRC’s) based at RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire and at RAF Boulmer in Northumberland. The CRC’s receive and process information provided round-the-clock by military and civilian radars to produce the RAP. In addition to this radar data, the CRC’s also exchange information using digital data-links with neighbouring NATO partners, AEW aircraft and ships. However, the production of the RAP is only one part of the CRC’s duties, the second being the control of aircraft.

The CRC’s are supported by three Reporting Posts (RP’s) across the UK. In addition to those found at the CRC’s, the locations of these RP’s reflects the locations of the RAF’s main Air Defence radars that feed information into the UK ASACS. These Reporting Posts are located at: RP Portreath which is a satellite of RAF St Mawgan, RAF Staxton Wold and RAF Benbecula in the Hebrides. A Reporting Post at Saxa Vord closed in 2005 and another at Bishopscourt in Northern Ireland closed in the late 1990’s

RAF Portreath also now acts as a training and development base for the Cornwall County Fire Brigade incorporating the Commercial & Industrial Training Section which offers a range of training courses for commerce and industry.

RAF PORTREATH TODAY

The Sector Operations still stands on Tregea Hill close to a new residential development and on the east side of the prominent Victorian incline that brought a branch of the Hayle Railway into Portreath.

The SOC saw little use during WW2 opening in July 1943 to replace the earlier SOC at Tehidy Barton Farm. It closed in late 1944 and was replaced by the Exeter SOC at Poltimore Park (this later became the administration block for the ROC Group HQ. The site was considered in 1961/2 as a civil defence control centre for the West Cornwall area but the cost was prohibitive and the building remained empty until 1977 when it was bought by its present owner who turned the operations room into a licensed leisure complex known as the ‘Ops Room Inn’ incorporating a dance hall. The Ops Room Inn closed in 1996 due to lack of patrons and the building is currently being converted into a number of flats. An additional floor has been added at one end of the building and the entire building has been given a new hipped roof. An integral lookout tower at the back of the building has been retained and incorporated into the conversion.

At the time of writing the operations room has been partitioned but is still recognisable with an office with a window overlooking the operations well still in situ. An adjacent room still retains the engine beds for a standby generator. The WT station for the SOC is also still extant on a private cliff ledge to the rear of Battery House above Portreath. This building can only be accessed from a steep overgrown path in the rear garden of Battery House and consists of a small rendered roofless building still within a fenced compound.

Much of the WW2 domestic camp is still extant along the north side of Penberthy Road (B3330) to the south of the airfield. Many of the buildings have been refurbished as light industrial and retail units while a few are now in residential use. On the airfield one runway remains active and this is used occasionally by Royal Air Force and Royal Navy helicopters. Most of the WW2 buildings were demolished following the closure of CDE Nancekuke but some original buildings survive. These include the combined mess, squash court, ambulance garage (behind the new Station Headquarters) and a number of refurbished huts near the main gate which have now been put to unspecified use. The aircraft machine gun ammunition magazine also still stands on the airfield close to the present transmitter block.

18 covered air raid shelters are also still extant (there were originally 19 but one has been demolished). These are of a unique design, internally similar to the Stanton shelter generally found at airfields with a walk in entrance down steps at either end leading to a single room about 25 feet in length. Unusually at Portreath the shelters have 12 external ventilation stacks in two lines along each side of the roof. These shelters are all in good dry condition and some are even lit. One of these shelters has been incorporated into a ‘Cornish Hedge’. (a stone faced earth bank often forming a field boundary in Cornwall).

The present radar is a Type 101 now housed beneath a Kevlar radome for added protection against the weather. The bunker is set into the side of a small valley on the south side of the airfield and is not visible from outside the perimeter fence. The bunker is semi sunken with an open front and earth cover to the rear with protruding intake and exhaust ventilation shafts.

Both the main personnel entrance and the plant entrance/emergency exit are located at the front of the bunker. The personnel entrance is at the end of a right angled open walkway and consists of a wooden door immediately followed by a steel blast door. This opens onto a lobby with a turnstile ahead and a police picquet room to the left. Once through the turnstile there is a left turn into the main east - west spine corridor.

The Comcen is on the right with its data transmitters relaying the data from the radar to the CRC’s at Boulmer and Scampton. Beyond this is the BT frame room and then steps down to the lower plant and domestic areas. The air conditioning plant room is next on the right and is still fully functioning although at a reduced capacity. The next room houses the Atlanta standby generator and control cabinets. The generator is still tested once a month. From here the corridor turns to the left through a large blast door which also acts as an emergency exit. Beyond this there is a dog-legged open walkway back to the front of the bunker.

Returning to the main spine corridor, the first room on the left is the police guard room and beyond it the computer room which is still in use. Beyond this is a workshop. At the back of the workshop is a corridor into the 1992 extension to the bunker which incorporates a number of rooms including the buffer power supply room which still retains its power smoothing machinery.

Beyond the workshop the next room on the left is the former operations room. This originally housed two rows of universal display consoles but these were removed when the station was downgraded to a remote radar head with only the controller’s desk, computer and electrical switch gear still remaining at one end of the room. Back in the main corridor the domestic rooms are at the bottom of the stairs on the left comprising male and female toilets, rest room and the site manager’s office.

Sources:

- Bob Jenner

- Keith Ward

- Ian Collett (owner of the Treganea Hill SOC)

- Action Stations Volume 5

- Airfield Review Volume 5 No. 3

- Secret History of Chemical Warfare by N J McCamley - Pen & Sword 2006 ISBN 1 84415 341 X

- Cold War Building for a nuclear confrontation by Wayne Cocroft & Roger Thomas - English Heritage 2003 ISBN 1 873592 69 8

- Nancekuke Remediation Project