Hydraulic Power in London

As a subject hydraulic power might not seem to have much connection with subterranea - until you realise that the high pressure mains ran below ground. This is an ‘entry level’ guide to the subject, with links to a number of other websites.

HYDRAULIC POWER - ITS NATURE AND USES

The secret of the utility of the hydraulic mains lies in the fact that water is virtually incompressible, and is therefore an ideal agent for transmitting power from one place to another. In London, water power was transmitted through a vast network of hydraulic mains to thousands of hotels, shops, offices, mansion blocks, hotels, docks and factories. Hydraulic power played an important part in the operations of lifts and cranes, but there were many other purposes for which the great pressure of the water was and still is used in industry.

Water power in London was controlled by the London Hydraulic Power Company, incorporated by Acts of Parliament between 1871 and 1903. Until it closed in 1977, the company supplied water at a pressure of 700 lb. per sq. in., day and night, all the year round, through some 150 (180 before the war) miles of cast-iron and steel hydraulic mains laid under the streets of London. This great labyrinth of power lines was not built in weeks or months, and the gradual spread of the silent tubes went on for more than half a century. The number of gallons of water pumped each week through the company’s mains in 1893 was 6,500,000; water pumped through the mains in 1933 averaged 32,000,000 gallons weekly. The mains were carried across the Thames at Vauxhall Bridge, Waterloo Bridge and Southwark Bridge. They cross under the river through Rotherhithe Tunnel and the Tower Subway beneath the Pool of London.

Before the LHP Company reached its zenith many dock and railway undertakings in London generated their own hydraulic power, using steam pumping engines and conspicuous ‘accumulator’ towers for storing this energy. A few such towers can still be seen, such as one close to the north end of Tower Bridge. Tower Bridge itself was operated by hydraulic power and the huge steam engines can still be seen in its engine room, now a museum.

Once the London Hydraulic Power Company’s mains spread out, covering much of London, and provided reliable service most users abandoned their own generators. Since the demise of the LHP Company the wheel has turned full circle, forcing users to install their own plant or convert to electric motors.

Applications for the enormous power of the hydraulic ram were manifold; it was used for cranes and lifts and could also be applied in presses for forging, stamping or flanging. At one time hundreds of such presses were in use throughout warehouses for baling cloth and paper, and for compressing scrap metal and other materials to facilitate transport.

THE LONDON HYDRAULIC POWER COMPANY

The Wharves and Warehouses Steam Power and Hydraulic Pressure Company was formed in 1871 to operate in London’s Docklands. In 1884 this became the London Hydraulic Power Company, providing hydraulic power over a wide area for the operation of lifts, cranes, presses and similar equipment. Central pumping plants supplied high pressure water to a pipe network, which was extended progressively up to the outbreak of war in 1939. For many years, up to the general adoption of small electric motors, hydraulic power was the simplest and most reliable means of operating a wide range of plant and machinery: at its peak, the Company was pumping more than 1.6 billion gallons of water annually at 700lb per square inch, supplying more than 8,000 machines. Wartime bomb damage, and the departure of many manufacturing firms from Central London, led to a decline in the Company’s activities postwar and despite a programme of electrification, pumping ceased in 1977. Control of the Company was acquired in 1981 by a group led by Rothschilds, which recognised the importance of the pipe network for the coming generation of communications systems. The network of 150 miles of pipes, ducts and conduits was sold in 1985 to Mercury Communications Ltd, now owned by Cable & Wireless Ltd, and since that time many miles of optical fibre cable have been laid in this network.

Replacing LHP Co. hydraulic mains in Piccadilly around 1930. The original cast-iron pipes with oval flange spigot and faucet joints are being removed and replaced with new steel pipes using Victaulic joints. Mercury Communications press photo.

Most of the pipes run just below the streets, although an important linking main ran through the old Tower Subway beneath the Thames (just west of Tower Bridge). Hydraulic power raised the curtain at the Royal Opera House, rotated the turntable at the Coliseum, raised lifts at the Bank of England (and thousands of other offices and flats) and opened dock gates on the Thames. In its heyday the company’s hundreds of workers pushed out up to 30 million gallons a week at 850 pounds per square inch from its six pumping stations. Then everyone from hotels, gasworks and rail depots to the Tate Gallery, Tower Bridge and West End theatres used the system wherever lifting power was needed.

Soon before the redundant piece of Victorian high technology was bought by a business consortium for £1.2 million, the company’s managing director, Albert Heron, who had been working for the company since 1935, was in command of just half a dozen staff, who carried out maintenance on the pipes, ranging in diameter from 2 inches to l0 inches. He told a reporter: “‘The cast-iron pipes are in excellent condition. The six-inch pipes are one inch thick”

The system covers an area from Kensington in the west to the East End docklands. Five pumping stations at Wapping, Bankside, Pimlico, City Road and East India Dock were closed, the sixth at Rotherhithe acting as the LHP Co. headquarters.

“All the machinery went for scrap, no one took any notice when we advertised it for sale,” said Mr. Heron. “Now a lot of industrial archeologists are crying crocodile tears.” The system’s death knell was sounded in the 1950s when the Port of London Authority and the Gas Board turned to other methods and the big rail depots moved from central London. “Now it’s like waiting for a rebirth,” said Mr. Heron. “I’m looking forward to business bucking up again.” [Adapted from The Free Weekender, 25th September 1981]

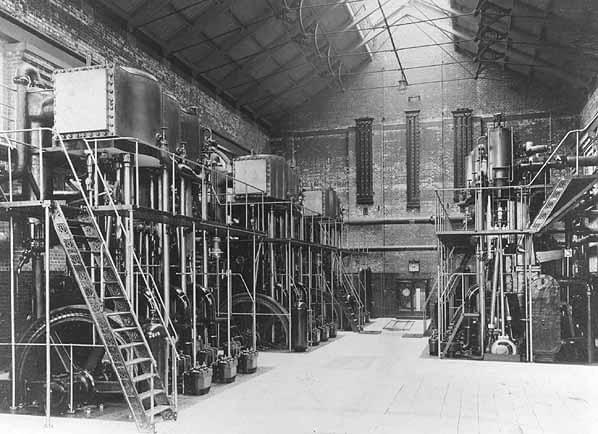

Engine room of the LHP Co. Grosvenor Road pumping station in Pimlico. The photo was taken in 1910, when the station was almost complete. The triple expansion steam engines drive high-pressure pumps. Mercury Communications press photo.

WHAT’S LEFT TO SEE

Not a lot is the simple answer. The Grade II*-listed Wapping Hydraulic Power Station on Wapping Wall has been transformed into a successful cultural amenity that has attracted international interest and has been compared favourably with the nearby Tate Modern. It was opened in October 2000 and belongs to the Women’s Playhouse Trust. It was built by the London Hydraulic Power Company in 1892 to supply hydraulic power for lifts and industrial uses and finally closed in 1976. When first built, the pumping station was steam driven. Two electric turbine pumps were added in 1923 and the whole station was modernised and converted to electricity in the 1950s. When the power station finally closed it was said to be the last of its kind in the world. The London Docklands Development Corporation was unable to find a suitable use that retained the original pumping equipment until the building’s purchase in 1998 by the Women’s Playhouse Trust. It now houses a restaurant, bar and exhibition space, enriching this formerly overlooked part of London.

Typical accumulator tower for storing hydraulic power. This one is close to the Royal Mint where the LTS railway line from Fenchurch Street crosses Mansell Street. The faded lettering on the side of the tower proclaims ‘London Midland & Scottish Railway City Goods Station and Bonded Stores’. Photo taken in April 1975.

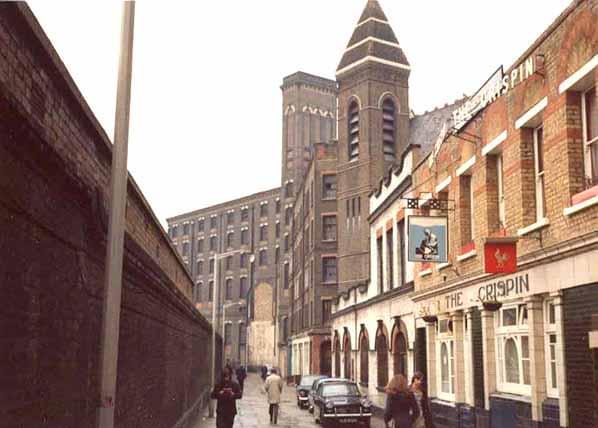

Can you spot the characteristic accumulator tower in the background? This is Wilson Street warehouse, seen from Finsbury Avenue. Photo taken in April 1976.

Over the years GLIAS, the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society, has done a grand job recording hydraulic installations. A search of their website will bring up useful data.

Two installations that survived into the 1970s were lifts. At Union Bank Chambers, 61 Carey Street, WC2, the main passenger lift operated on a hydraulic ram, with electric press-button control. With passengers aboard the lift car traveled at normal speed but when called from rest, the ram propelled the car at a truly unnerving rate of knots. The Grosvenor Hotel, adjoining Victoria station, had a service lift of a very antique character. It still used rope control (you pulled up or down on the rope to start the lift and held it to stop). It operated at two speeds, depending on your pull. There was no self-levelling at each floor but auto-stop trips at the top and bottom of the shaft prevented over-run. Electrical interlocks had been retro-fitted to the lift car’s doors. After the LHP Company went out of business, the system was converted to oil, using an electrically driven compressor. Whether these two installations survive is unclear.

REAL HISTORY

Mr Charles Keeble writes: “The reason that I am writing to you is that at one time when I lived in London, I worked for LHP at 80 Grosvenor Road, Pimlico, where one of the pumping stations stood at the rear of the workshops. The workshops were on two floors; the machine shop was in the basement to road level, which turned the rams and cylinders, and the top shop we used for the building of lift cars.

I started working there in 1961 till 1968 and I was 17 years old at that time. I started as a turner improver and progressed to fabricator welder.

I worked on the Tower Subway at Tower Hill, where I fitted a new chequer plate floor. I did not know at that time the history of the subway until I got on to your website.

I also was on mains call out and when we had a leak, nine times out of ten it would blow up the road. Then I would get all my cutting gear ready to go out to cut out the section of pipe. Sometimes they would put steel plates over the hole to keep the traffic moving, while I was underneath cutting out the pipe.”

Front view of the LHP Company’s premises in Grosvenor Road, Pimlico in the mid-1960s.

The premises at 80 Grosvenor Road went under the name of HYPOWER. When I left in 1968, we were making hydraulic rams for the main shield for the Victoria Line for the section between Brixton to Victoria. which was started in Bessborough Gardens on the north side of Vauxhall Bridge. Where a 100ft hole was dug to go under the river to Brixton and Victoria, it now remains as a vent.

ESSENTIAL READING

- Jarvis, Adrian: Hydraulic Machines. Shire Publications, 1985. Low-cost photo album with very good text.

- Pugh, B.: The Hydraulic Age. Mechanical Engineering Publications, 1980. Historical survey.

- McNeil, Ian: Hydraulic Power. Longman, 1972. Volume in the highly respected Longman Industrial Archaeological Series.

- There is also a paper by Ralph Turvey, ‘London Lifts and Hydraulic Power’ in Newcomen Society Transactions, Vol 65, 1993-94, 147-164, which is in part a history of the LHPCo, and includes a comprehensive bibliography.

- The Science Museum Library also has a map of LHPC pumping stations and mains, published by the Company in c1950, and there is an article by Tim Smith, ‘Hydraulic power in the Port of London’, published in Industrial Archaeology Review, Vol 14, no. 1, Autumn 1991, 64-88.

- Thanks to John Liffen of the Science Museum for assistance with this list.